MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker 04/2023

Introduction

2024 will be a geopolitically complicated year, with elections in Taiwan, the United States, and to the European parliament. Two other key global players, India and Russia, are also due to hold elections. We will enter the new year in an environment of worsening geopolitical and technological competition, and with wars raging in Ukraine and Gaza. Europe-China relations showed few signs of improvement after the December 7-8 EU-China Summit in Beijing. China’s own economic prospects are rocky and Beijing will need to address domestic social fault lines.

To help European actors anticipate what 2024 may bring, MERICS has developed a foresight effort to identify key China risks. We sought to pinpoint risks with the biggest impact on European interests and security. We ran two separate, off-the-record foresight workshops in mid-November hosted by MERICS in Berlin. The first workshop consisted solely of MERICS experts, while the second brought together some 15 European officials, business representatives and external experts. The process will be repeated annually.

MERICS Top China Risks 2024 consists of the most probable and highest impact risks we identified in these sessions. These risks have urgent implications for European policymakers. We will track them throughout the year in upcoming editions of this MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker.

Nor will we lose sight of risks which the two expert groups thought less likely to materialize in 2024 but which would have major implications in Europe. Some are included as ‘what ifs’ in this publication. However, they were not the only other risks identified in discussions. Escalation in the South China Sea is a possibility, with a possible trigger point when the Philippines’ rusting, grounded ship in the Second Thomas Shoal (the Sierra Madre) disintegrates.

For foreign firms, China’s changing regulatory environment poses greater risks of local staff becoming tangled up in investigations or arbitrary detention. Severe climate events in China in 2024 may drive up global food and energy prices. And Beijing’s continued reluctance to implement structural reforms needed to revitalize economic growth will impact consumption rates and worsen conditions for foreign businesses in China.

European actors should brace for greater risk and uncertainty in their relations with China next year. Efforts to stabilize relations and find new avenues for cooperation with Beijing will continue, but the overall outlook is a challenging one.

Top China Risks 2024

China’s exports will flow into Europe in greater quantities next year. The country’s economic trajectory could begin to undermine Europe’s manufacturing base. Beijing directed considerable investment resources into manufacturing and technology upgrades in 2023 to drive growth and counteract China’s stagnant consumption and a sluggish real estate sector. As a result, China now has more manufacturing capacity, especially in high-tech and new energy sectors, including EVs. Structural reforms that could support household consumption and absorb these goods do not feature on President Xi Jinping’s economic agenda. We therefore expect China’s manufacturing overcapacities will continue to grow in 2024 and Beijing’s only option to deal with them will be exports.

More Chinese exports to Europe will worsen the imbalances in the economic relationship: the EU’s trade deficit with China is currently at almost EUR 400 billion. As happened with the solar panel industry in the early 2010s, European manufacturing will be undercut by heavily subsidized Chinese exports unless it is defended from market distortions. The automobile industry is already feeling this trend as Chinese EVs and EV batteries are rapidly entering the European market. Other industries will feel the heat next year too. In the green tech, white goods, steel and cement industries, China’s overcapacity is compounded by its real estate crisis.

Together with China’s push for self-reliance, this paints a difficult picture for European businesses in 2024. It will worsen considerably if Europe acts slowly while other major markets - like the United States, Japan, and India - take swift action to shield their markets from these distortions, leaving Europe as among the few remaining pressure valves for Chinese overcapacity.

The United States will go into election mode in early 2024 as both parties start the process to select their presidential candidates for the November vote. China has become a US domestic political issue so it will play a key role during the campaign. Candidates on both sides of US politics will compete to display their toughness towards China, risking tensions with Beijing. A victory for ex-president Donald Trump (or another Republican) could lead to a reorientation of Washington’s China policy, most likely veering towards intensified competition with Beijing and far less alignment and coordination with allies and partners.

Europe will find itself having to navigate a shifting geopolitical environment while transitioning into a new European Commission mandate after its own June 2024 European elections. The EU will need to find a way to triangulate its own position between the two powers. In the US, the focus on the November election and its internal processes will erode attention to transatlantic coordination. Meanwhile, Beijing is pushing a charm offensive in Europe to drive a wedge between the transatlantic partners. Brussels will need a clear strategy to defend European interests. Without it, Europe risks loss of agency and a reduced ability to deliver on its own key interests independently.

The EU has made great progress in building consensus on the challenges China poses to European interests and security. However, European responses still lack cohesion and these gaps will create risks. Between the June 2024 elections and a new Commission taking office in the fall, divergences between member states and EU institutions will come to the fore. There is a risk Beijing will exploit the transition by seeking to stall or derail the EU’s China agenda next year.

2024 is likely to see China continue its charm offensive towards Europe – or towards selected member states. Just like after the December 2023 EU-China Summit, Beijing might try to present the resumption of dialogues and exchanges as a deliverable in itself, proof that EU-China relations are getting back on track. This narrative attempts to obstruct further action on the EU’s de-risking agenda by presenting it as disruptive to mending relations. It may find traction in some member states, where the debate leans towards fear of Chinese retaliation against a more assertive European approach. The EU’s ability and resolve to use its new economic policy instruments may be tested, notably the Anti-Coercion Instrument which comes into force on December 27.

Beijing’s initial response to US export control measures targeting China’s tech sector in 2023 was relatively muted. Gradually, the elements of Beijing’s strategy for industrial defense and retaliation against tech trade restrictions became clearer. China’s cybersecurity review into US memory chipmaker Micron and new export controls on key minerals gallium, germanium and graphite showed Beijing testing an arsenal of regulatory and legal tools that it had patiently built up over a decade.

Worsening US-China relations and the EU’s de-risking strategy elevate the risk that Beijing will threaten to deploy its toolkit of instruments. It may weaponize dependencies by turning to export controls on critical raw materials it has a near-monopoly on. These threats could come as tit-for-tat responses to more US export controls, or as a unilateral move by Beijing to obstruct Western countries’ efforts to reduce dependencies on China. Many of the critical inputs China might target are vital to the EU’s green and digital transitions.

China’s economic situation, and the volatile wider geopolitical context in 2024, might equally well prompt Beijing to take such actions, or to favor the known scenario and stick to making coercive threats. This is likely to depend on US-China dynamics and Beijing’s wish to preserve its own leverage. However, any curbs on critical supply chains would hurt European industry and European interests more broadly. Even if China’s measures were not directly targeted at Europe, the EU would find itself caught in the crossfire given how deeply global tech supply chains are interconnected.

Beijing and Moscow will continue to strengthen their relationship. The two sides will reaffirm their joint geopolitical position vis-à-vis the United States and its allies, and Chinese support will enable Moscow to help the Russian economy stay afloat and continue the war in Ukraine. While Beijing is unlikely to deliver a substantial quantity of lethal weapons to Moscow, exports of Chinese commercial drones and dual-use tech and components will continue next year and are likely to expand.

The EU will have to decide if increased Chinese support for Russia’s war machine crosses its red lines, even where no lethal weapons are involved. If the answer is yes, Europe faces a hard choice. It can take action against the Chinese firms involved, shouldering the economic costs and Beijing’s likely economic retaliation, or ignore its own red lines and erode its global credibility.

There will also be greater Beijing-Moscow coordination within the United Nations system in 2024, generating new risks for European actors. The EU and its member states must anticipate that China and Russia will work hard to reshape and redefine aspects of the rules-based international order. More and better coordination with Europe’s like-minded allies and partners is needed to push back against these efforts.

Next year, China will remain reluctant to get meaningfully involved in conflict spots, from Ukraine and Israel to Myanmar and Afghanistan, or to behave constructively to achieve lasting solutions. Beijing will continue to present itself as a responsible global actor and offer to mediate, but concrete action will not be forthcoming. The Chinese leadership still views these conflicts primarily through the lens of its competition with the United States; it is reluctant to accept the risks that come with wading into complex, entrenched conflicts.

It will continue to leverage these conflicts to discredit the West at large next year and to push its own coalition building efforts in the Global South. Beijing’s narratives blaming the West for global instability are finding a receptive audience in many developing countries and hurting Europe’s geopolitical standing. This trend will only worsen in 2024, especially if the wars in Ukraine and Israel continue.

China’s approach will hinder efforts to restore stability and to prevent further escalation. It will also narrow the space for dialogue or cooperation with China on any form of conflict resolution efforts further. For Europe, there is a risk of expecting too much from China, and of hoping for a shift if Beijing is pressured enough. This is unlikely to work as Beijing still prioritizes the geopolitical struggle with the West over any benefits it might derive from contributing to the resolution of these conflicts.

What if...

Europe should keep an eye on other risks and developments that are less likely to materialize in 2024 but could still have a strong impact on European interests.

… a conflict breaks out in Taiwan after the January presidential elections?

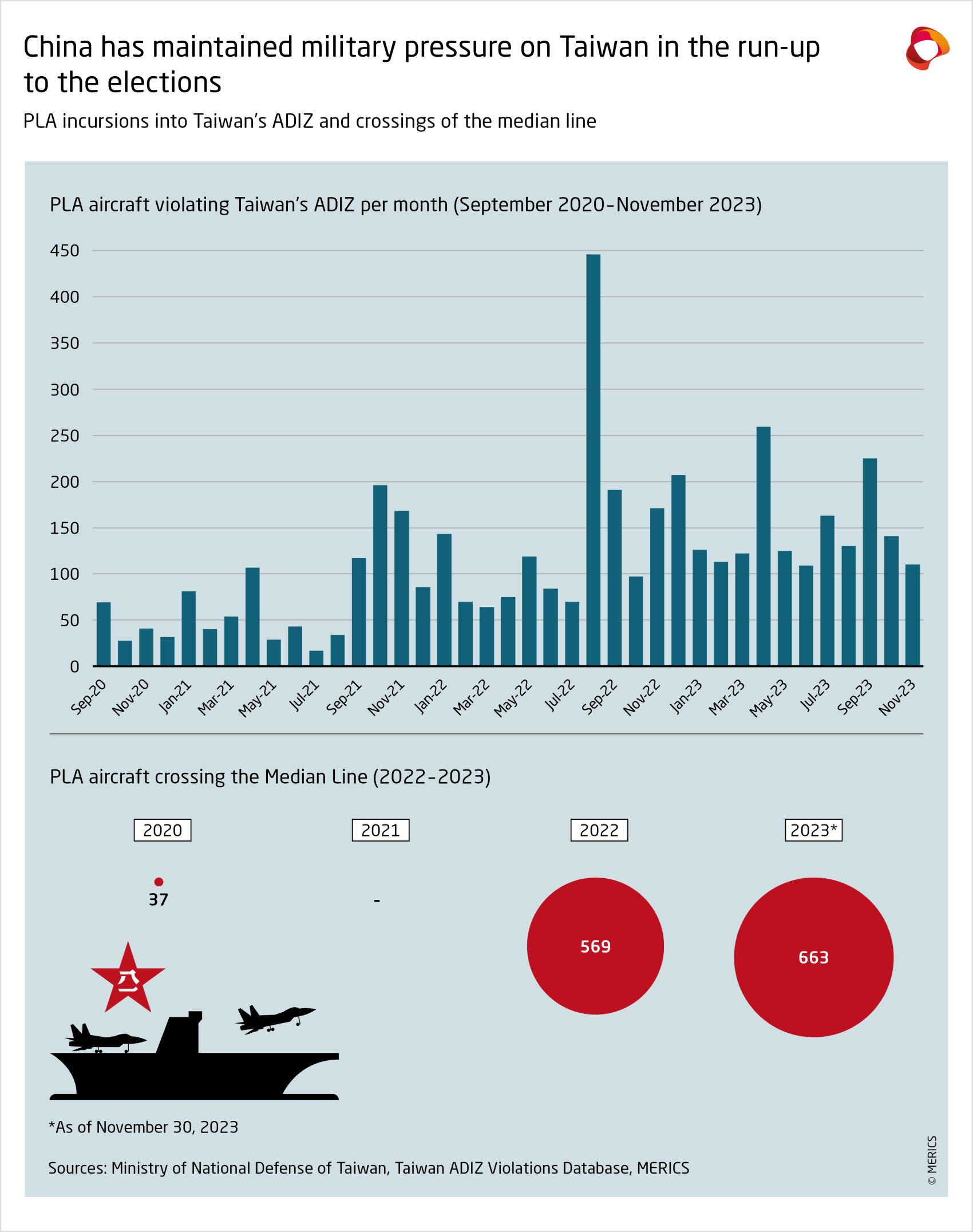

Open conflict in the Taiwan Strait is unlikely in 2024, regardless of who wins the January presidential election. Beijing regularly attacks the DPP as “separatist” (as it has since Taiwan's outgoing president Tsai Ing-wen won for the DPP in 2016). But it is likely to take a wait-and-see approach to Taiwan ahead of the US elections. Its most likely response if the elections do not go its way would be yet more PLA activities in the region, and greater economic restrictions against Taiwan. This would bring higher tensions and volatility. An all-out conflict is unlikely. However, if one were to break out unexpectedly it would have a huge impact on European interests and security and would catch the EU largely unprepared.

… a deep real estate or debt crisis hits China’s economy?

China’s economy is in a bad state, with the real estate sector in crisis and soaring local government debt levels. The central government has access to a variety of tools to prevent a full collapse next year, and there is limited risk of contagion given the restricted interconnections between Chinese and European financial systems. But if a deep real estate or debt crisis does materialize, China’s already muted spending on domestic consumption spending would fall even lower. The economic spillovers would not just hurt European firms with a presence in China, but also European exports and global economic growth.