MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker 03/2024

China signals its willingness to play a proactive role in Russia-Ukraine relations, if conditions are suitable

by Eva Seiwert

China has spent much of this year signaling that it is ready to play a more proactive diplomatic role should Moscow and Kyiv deem conditions right to discuss a negotiated settlement. Part of this process consists in promoting a peace framework and narrative that suits Beijing’s interests.

China published its 12-point "Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis" in February 2023, ending its conspicuous silence in the first year of the war. Since then, Beijing has sent its Special Representative on Eurasian Affairs, Li Hui, to discuss the Russia-Ukraine war with governments in Europe, the Middle East and, over the summer of 2024, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia. In July, it welcomed Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba to Beijing as the first high-ranking Ukrainian official visitor since the start of the war. Kuleba spoke of a “clear sign that China is working to end [the] war in Ukraine” – only weeks after China skipped the Peace in Ukraine summit in Switzerland in June, with Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelenskyy even accusing Beijing of boycotting it.

China now campaigns for a new peace conference that includes the “equal participation of all parties”, as outlined in a further six-point proposal in May - published jointly with Brazil - on the “political settlement of the Ukraine crisis”. With other countries, including India, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Kenya, also lamenting Russia’s absence from the Swiss summit, China has been presenting the six-point-plan as a more promising roadmap to peace and one with the additional merit of being led from the Global South. On a visit to Brazil in late July, Li reported that 110 countries had already supported it.

Beijing sees advantages in becoming more involved

China’s growing presence in discussions around the Russia-Ukraine conflict is driven by several factors. First, Beijing wishes to be seen as a more constructive player, which may be a response to continuing Western criticism and to sanctions on Chinese companies helping Russia’s war efforts. Offering its own proposals, however vague, enables Beijing to dismiss accusations of pro-Moscow bias and show willingness to engage in conflict resolution. It may also hope to sidestep criticism and avoid further sanctions.

Second, China may be positioning itself to take advantage of potential shifts in US foreign policy after the US presidential election in November. If Donald Trump beats Kamala Harris, the United States could end or reduce military assistance to Ukraine (some USD 55 billion since 2022) and leave Kyiv in a precarious position on the battlefield. Beijing knows this and seems intent on exploiting the current uncertainty to steer Kyiv towards peace negotiations that align with Chinese interests. Foremost of these is to place limitations on NATO influence beyond its current borders. Beijing may also see a more proactive role as a way to bring some improvements to its strained relations with Europe.

Finally, China wants to enhance its image as a globally responsible power and a representative of the Global South. Many countries in the Global South regard China’s approach to the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Palestine conflicts as less controversial than Washington’s, which faces criticism for double standards in its approach to the two conflicts. Furthermore, Beijing was instrumental in getting Iran and Saudi Arabia to resume diplomatic relations in 2023 and Hamas and Fatah to pledge Palestinian unity in July. Beijing wants to build on these successes by presenting itself as a more reliable and less controversial broker than Washington, thereby burnishing its standing and bolstering its wider ambition to reshape the global order.

The China-Russia partnership can complicate Beijing’s plans

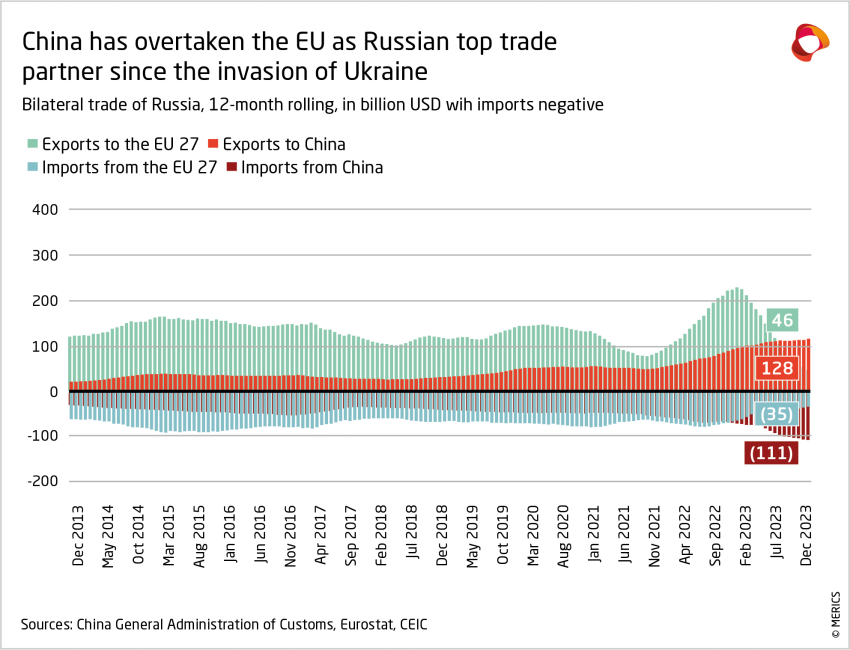

But China’s close partnership with Russia will complicate any peace-making role Beijing seeks with Ukraine. Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin signed a joint statement in May on deepening the China-Russia “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era”, a laudatory label that China has used only for its relationship with Russia. The two countries regularly conduct joint military exercises, as many as 22 since February 2022. Meanwhile, Beijing supports Moscow’s war, at least indirectly, by providing vital dual-use goods and strengthening bilateral trade ties.

Yet, while this stance is controversial in the West, many in the Global South have chosen a similar approach of neither recognizing Russia’s illegal annexations nor condemning Moscow’s actions. India, Brazil, South Africa, Turkey and many other states have refrained from imposing sanctions on Russia and maintained, or even strengthened, trade relations. However controversial China’s positioning on Russia-Ukraine is in Europe and the United States, many governments elsewhere are less wary. Still, it should not be forgotten that China will always advocate for a solution in line with its own vision of a reshaped “fair and reasonable multipolar world,” which it shares with only one of the conflict parties, Russia.

Beijing is preparing for a more active role

Ultimately, only Russia and Ukraine can decide to what extent China can influence the war. Only they can decide if they want peace talks and whom to accept as mediator. At present, neither seems inclined to negotiate an end to the war and both have sent mixed signals about China. Despite Kuleba’s praise for China, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has said Beijing should apply more pressure on Moscow to end the war, not act as a mediator. Moscow has been equally unclear whether it would support China playing a bigger role.

Beijing currently has little leverage to alter Russia’s position, and even less so Ukraine’s. Based on Beijing’s previous approaches to conflict resolution, its role – if it materializes – would likely be limited to providing a setting for negotiations and bringing the parties to the table (as it did with Saudi Arabia and Iran), possibly within a wider multilateral effort that highlights its close relationships with other countries of the Global South.

Beijing’s recent diplomatic activities are intended to signal its openness to playing a more proactive role if asked by Ukraine and Russia. Beijing seems to be getting itself ready for the eventuality though, like everyone else, it cannot know if or when the combatants might indicate a willingness to negotiate an end to the war, or to accept China’s facilitation.

Top China Risks 2024

The likelihood or probable impact of some of the 2024 top China risks identified by MERICS in late 2023 continues to shift. The US Democratic Party’s changed presidential ticket, combined with both parties’ vice-presidential choices, has changed expectations on Washington’s likely China policy, whoever forms the next administration. The final vote on the EU’s tariffs on Chinese EV imports will challenge the bloc’s cohesion. And recent developments in China-Russia cooperation, and Beijing’s growing role in other conflict mediation efforts, could create new challenges for Europe. Below, we outline some key developments that have altered our risk assessments.

Election season in the United States

Both US presidential candidates in the November elections view China as a major threat, but their approaches differ. The vote will therefore result in divergent China policies, depending on whether Donald Trump or Kamala Harris wins, and will have significant implications for Europe.

The Harris-Walz campaign has yet to fully clarify its foreign policy, though Harris has pledged to “stand strong with Ukraine and our NATO allies” and ensure that “America, not China, wins the competition for the 21st century.” Debating with Trump, Harris criticized Trump’s trade war with China, signaling a likely continuation of the Biden administration’s “small yard, high fence” strategy, which emphasizes targeted tariffs and export controls. This approach could pressure Europe to align with broader US technology restrictions on China. Harris also takes a tougher stance on Russia, viewing the war (and the possibility of Ukraine’s defeat) as a critical threat to European security. In the broader context of countering China, Harris and her team consider a strong US presence in Europe as essential for deterrence, including in the Indo-Pacific.

Trump and J.D. Vance, on the other hand, prioritize countering China more unilaterally through an "America First" approach, which could pose more direct risks to Europe. An aggressive tariff war under Trump could strain European efforts to balance economic ties with China against security reliance on the United States. Increased transatlantic trade frictions are also likely. Trump's insistence that European nations “pay their fair share” for defense or Washington may reduce its commitment to NATO could leave the Alliance divided and vulnerable. On Ukraine, Vance advocates halting US military support to Kyiv to focus on countering China, a shift that would force Europe to find ways to increase support for Ukraine, or risk seeing Kyiv pushed to the negotiating table with Russia while lacking leverage.

Regardless of the US election’s outcome, Europe will need to prepare for adjustments in US China policy and transatlantic cooperation. A Trump victory may force tougher choices, particularly regarding trade and NATO funding, while a Harris administration would also pressure Europe to align more closely with US strategic interests in countering China.

European cohesion

On October 4, the European Commission obtained the support it needed from EU member states to impose tariffs on the imports of China-made electric vehicles (EVs). This is a win for the von der Leyen Commission, which launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs exactly one year before the vote, in a bid to tackle China’s unfair competition and its impact on the European market. Notably, Germany, the EU’s biggest economy and major car producer, voted against the tariffs.

But after six years of relatively solid cohesion among member states, the vote has also exposed the fragility of the union when it comes to China policy, as well as the weight of national interests in shaping decisions in this space. A breakdown of the vote shows that not all member states perceived this decision as the most adequate response to the problem at hand. With 10 Member States in favor, 12 abstaining, and 5 voting against, hesitation was apparent.

Looking at capitals’ explanations for their votes, it is clear that Europe has been divided into three main blocs. The first bloc has opposed the tariffs out of fear of Chinese retaliation against specific industries, or out of a strong belief that free trade needs to be protected at all costs. The second bloc – comprised mostly of countries that abstained, although some also voted against the measures – seemed to believe that more Chinese investments and economic benefits would materialize for their country if they tried to balance Brussels’ decision. Lastly, a third bloc has supported the EU’s decision because they have experienced the consequences of China’s unfair practices, or because they see this is a rather limited price for China to pay for the market distortions it has created in Europe.

The EU should draw a few lessons from the vote itself and from the preceding process. First is that further fragmentation and divisions in European China policy are extremely likely. Given Germany’s weight within the EU and the leading role it plays in shaping the EU’s China policy, Berlin’s decision to vote against the tariffs could open the door for other Member States to take a similar stance in future votes. Additionally, the vote has also shown that China’s strategy of instilling fear of economic retaliation, particularly in sectors like agri-food, can be effective in shaping some capitals’ decisions.

Beijing has already expressed its anger at the result of the vote, and Europe must now prepare for possible Chinese retaliation, brace for this backlash and work to prevent fears of retaliation from driving European China policy going forward. Without this, European unity and credibility vis-à-vis China and its partners will be undermined.

China-Russia coordination

China and Russia marked the 75th anniversary of their diplomatic relations with a series of high-level consultations in Moscow in August 2024, which produced 25 agreements on issues from trade to artificial intelligence.

Beijing and Moscow signaled they have no intention of letting international pressure drive a wedge between them in their joint communique signed by China’s Premier Li Qiang and Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin. It emphasized the relationship is a “strategic choice” that is “not affected by changes in the international situation”.

They also used the celebratory consultations to strengthen cooperation on defense issues, with a particular focus on outer space. Moscow hosted the first consultations on the peaceful uses of outer space, building on the February consultations on outer space security. Both sides agreed to step up cooperation, including on the shaping of international law related to space.

Beijing and Moscow have been building up their space partnership for the past few years, recognizing space as an emerging arena of geopolitical competition (or a “strategic new frontier” in Chinese discourse). They have recently formalized plans to jointly build an International Lunar Research Station, possibly powered by a lunar nuclear plant.

The lack of transparency in China-Russia space cooperation makes it difficult to accurately assess the specifics and progress of the programs announced. But the growing number and increasingly sensitive nature of their agreements indicates a deepening strategic partnership. It is a partnership designed not only to make scientific progress, but also to be a counterbalance to US dominance in space and to develop (or expand) space-based capabilities with military uses. As geopolitical competition extends to space, there is a growing risk that space will become a fragmented and militarized arena, with serious implications for Europe’s security.

China’s role in international conflicts

In July, Beijing claimed another victory for its conflict mediation efforts. Fatah, Hamas and 12 other Palestinian factions signed the “Beijing Declaration on Ending Division and Strengthening Palestinian National Unity” in Beijing. China brokered the process, at the end of which all the factions apparently agreed to reconcile and set up an interim unity government under the authority of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

A meaningful, sustainable consensus between Palestinian factions would certainly be a substantial diplomatic win for Beijing. But there are reasons to be skeptical about the durability and practicalities of this deal. This is not the first time that Palestinian factions have agreed to collaborate, or even the first Beijing-hosted round of talks. More trust-building will be needed if all the factions are to work together going forward. Beijing has shown itself reluctant to get much involved with such implementation processes. Guaranteeing agreements and holding all parties to their commitments would entail too much risk exposure for China. There is little chance that China can expand this success into an Israel-Palestine mediation effort. China’s relationship with Israel has deteriorated rapidly since Hamas’ October 7 attacks into Israel. This new agreement also predates, and therefore does not consider, the current escalation of tensions in the Middle East.

However, China can certainly use its success in these negotiations to further its self-styled image as a peacemaker and responsible global power, different from Western nations, and to build support across the Global South. This approach was in full view at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), held in Beijing in early September. China offered to get involved in conflict resolution efforts in Africa as much as possible, and praise for China’s “great efforts in supporting the just cause of the Palestinian people” made it into the joint resolution. This highlights the impact of China’s narratives and successes – even limited ones– on perceptions of its global role compared to Europe’s or the West’s more broadly.

China's shifting regulatory environment

CHINA’S SHIFTING REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The Third Plenum confirms Xi’s vision for China’s modernization

On 19 July, the Central Committee of China’s Communist Party (CCP) concluded its third plenary session with a full-throated endorsement of Xi Jinping’s grand vision for a technology-driven socialist future. Rising social and financial tensions caused by China’s weak economy were reflected in adjustments to the messaging but there were few signs of compromise or any change of direction. High-quality economic growth, driven by technology, and focused on “new-quality productive forces”, and economic self-reliance under the leadership of the CCP is the chosen path forward.

The Central Committee also vowed to give greater support to the private sector; to improve social security; to ease the lot of rural migrants; to create jobs for university graduates; to reform the tax system and to rejig public finances thereby helping local governments fulfill their welfare obligations.

With 300 measures to be adopted by 2029, the CCP leadership showed that it is aware of China’s many current challenges. But there are good reasons to be cautious about the likelihood of consistent implementation. These pledges are in competition for the party state’s attention – and funding, a problem that got scant acknowledgement.

Over the next few years, the party will be focused on strengthening China’s capacity to go it alone and preparing the country for whatever crisis or conflict the future may hold. The Third Plenum showed the CCP’s willingness to sacrifice the economic gains of efficiency for the geopolitical benefits of greater resilience. For the majority of citizens and private companies, foreign ones included, nationalistic policies and increased geopolitical friction will bring continued challenges.

For more on this, see “Having it both ways – Third Plenum promises reforms and doubles down on Xi’s grand vision” by Rebecca Arcesati, Katja Drinhausen and

Max Zenglein

Looking forward: What to watch in the months ahead

- October 22-24: Kazan, Russia, will play host to this year’s BRICS Summit. After five new members joined the group at the beginning of the year, this summit will provide another opportunity for Beijing and Moscow to promote further enlargement. Turkish President Erdoğan is expected to attend after announcing in early September that Turkey is seeking full membership of BRICS.

- November 5: The United States votes to elect a new president, Congress and Senate. The results will impact not just Washington’s China policy, but also transatlantic relations and global geopolitical dynamics.

- November 11: Global leaders will gather at the Cop29 climate summit in Azerbaijan to tackle the thorny question of climate finance, among other key issues. Another attempt will be made to bridge the gap between China, Europe and the United States on this topic, but success seems far from certain.

- November 18: The G20 summit will take place in Brazil. Russia’ membership of the group and international tensions over the wars in Ukraine and Gaza are expected to cast a shadow over the proceedings.