EU economic security strategy + Li Hui's trip to Europe

Analysis

The EU’s economic security strategy is not about China until it is

By Francesca Ghiretti

Next Tuesday, June 20, will see the publication of a joint communication on EU’s economic security, also known as the economic security strategy. If you are expecting a short and snappy definition of economic security that will once and for all clarify what the EU means by the term, you will be disappointed. Labelled as the “EU’s economic strategy”, it is set to provide a framework for several policies the EU has and is set to adopt. It is also viewed as a way to open a debate on EU economic security and how to develop it.

The European Commission is committed to clarifying that neither the forthcoming strategy nor EU’s approach to economic security is about China. That is not new, the pushback against a China focus can be found in most debates regarding economic security policies such as foreign direct investment screening, the anti-coercion instrument and ultimately, export controls.

The pushback is often viewed as a way for the EU to avoid creating diplomatic tensions with China, even though the policies indirectly target China. There is an element of truth to that, but there is also an element of truth to the EU’s genuine support for a country-agnostic approach to economic security.

It may sound tautologic, but the EU’s economic security is about the EU’s economic security, meaning the priority is not to defend against or contain China, but to ensure the safeguarding of the block’s economic security. Accordingly, any country or actor that threatens that security is a target, and the targets can evolve over time. Let’s take the classic example of the EU’s anti-coercion instrument (ACI). It originally emerged in response to economic coercion from the US during the Trump administration. However, as China adopted economic coercion tactics against Lithuania, the focus has pivoted to the east. In the future, economic coercion against the EU or its member states could come from other actors and the instrument adopted will be equally capable to respond to all.

Furthermore, the EU’s economic security awakening has not been triggered by China. Undeniably, concerns related to China have played a major role in shaping many of the policies that fall within the framework of economic security. However, it was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the direct impact curtailed gas supplies from Russia have had on Europe that brought economic security front and center. Hence, the joint communication on economic security is likely to address such weaponizations of economic dependencies and linkages. China too has weaponized linkages and it may do so much more intensely or regularly in the future, but those past instances did not cause as much widespread pain as Russia’s did, and thus did not trigger the same response.

Thus, the EU’s approach to economic security is not about China because the EU sees China as a geopolitical rival, it is about China because China poses a series of risks to the EU (that span from national security to the lack of a level playing field and common understanding of rules) and the measures adopted, or that will be, seek to respond to these risks. That is why a solid risk assessment is the first step to a proper approach to risk management that could indicate how best to prioritize different issues (i.e., where do we invest first) and guide policies with sectoral and geographical focus. Such risk assessment should also factor in the costs of managing the risks, for example, how costly it will be for the EU to adopt diversification policies or to reshore certain supply chains, such as critical raw materials. Then, the risks should be cross-checked with existing policies and measures adopted to evaluate how resilient the EU already is in those categories.

That will guide the EU in how to better approach the strengthening of its economic security. Part of that approach will focus on how the EU works with partners. In fact, despite the commitment to maintaining an international rules-based order, there seems to be a reckoning even within the European Commission that plurilateral engagement with a selected number of countries may be a necessary parallel way forward. In many instances, that plurilateralism will not include China.

In conclusion, it is true that the economic security strategy is not about China, it is after all about EU’s economic security. However, it becomes about China when and only when China threatens European economic security and, in that sense, it is also about China.

Read more:

- Le Grand Continent: Construire la sécurité économique de l’Europe

- MERICS: From opportunity to risk : The changing economic security policies vis-à-vis China

- South China Morning Post: EU’s ‘de-risking’ plan for China meets resistance from some members

Update

Two visions of peace with a price tag – China’s Special envoy talks Ukraine war during tour of Europe

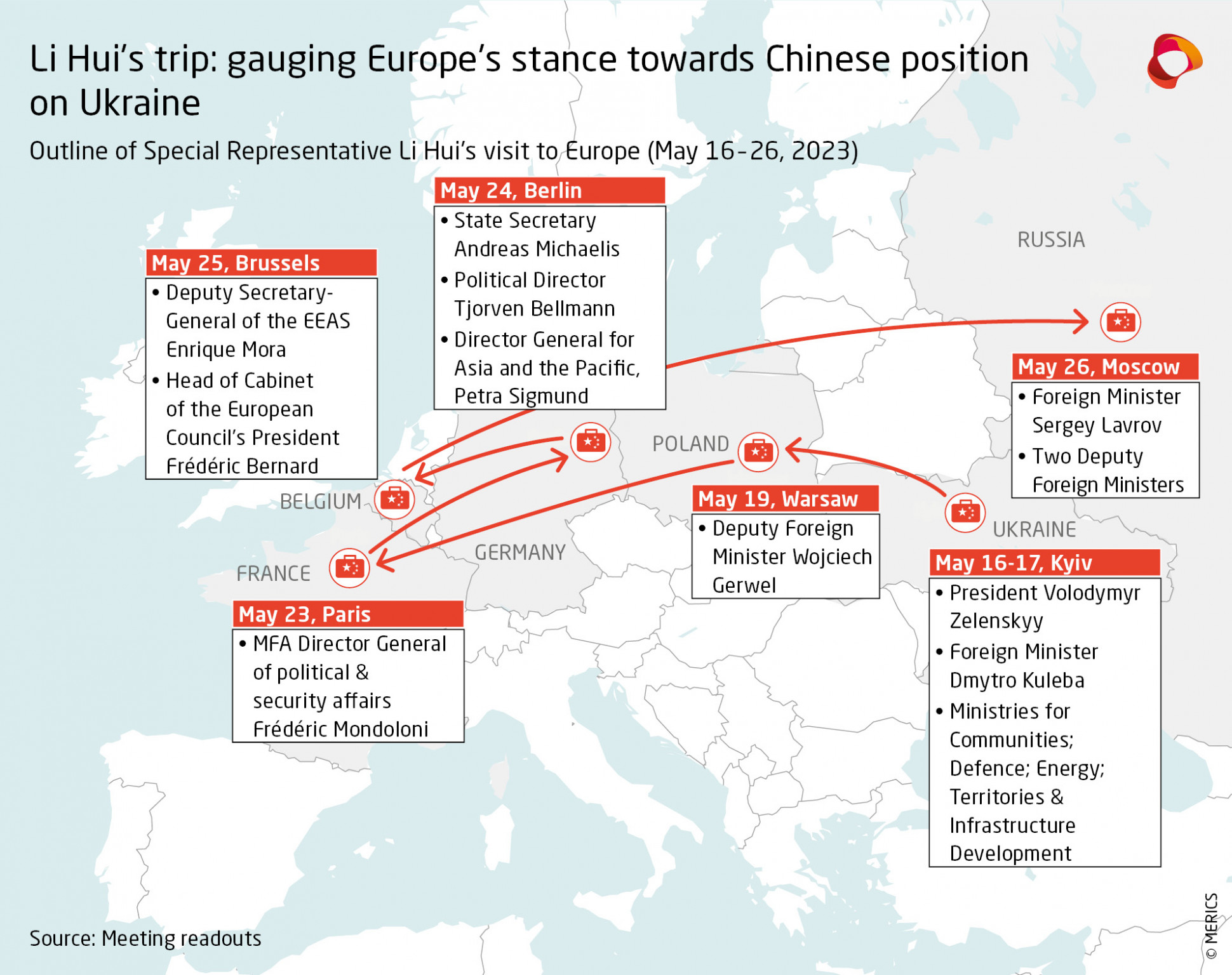

Following up on the call between Presidents Xi and Zelensky, China sent its MFA’s Special Representative on Eurasian Affairs, Li Hui, to Europe to talk “political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” Li’s 12-day trip took him to Kyiv, Warsaw, Paris, Berlin, Brussels, and Moscow, but bore little fruit and highlighted fundamental differences in China’s and Europe’s perspectives on the war.

What you need to know:

- Gauging Europe: By sending Li Hui – an experienced diplomat and former ambassador to Russia, but still not a key foreign policy figure – Beijing sought to test the water on the “Ukraine crisis” rather than engage in meaningful dialogue. Throughout the visit, Li primarily reinforced the Chinese points from the February position paper and gauged the reactions of European counterparts.

- Battle of narratives: Through its readouts, Beijing tried to push a message of supposed alignment with Europe on its proposal ignoring the apparent differences in the approach. All available European readouts (Germany has not released one) emphasized Russia’s full responsibility for the war and need to re-establish Ukrainian territorial integrity in accordance with international law. This sets them apart from Beijing’s position, that broadly validates Russia’s position by saying that all sides of the conflict have “legitimate security concerns.” Ukrainian pushback was clear with its Minister of Foreign Affairs stating that “Ukraine does not accept any proposals that would involve the loss of its territories or the freezing of the conflict.”

- Polish communication push: Among European readouts, the Polish one stands apart from the usual practice of European capitals’ engagement with China. Not only did it come out before the Chinese one but was also robust in outlining that Warsaw opposes attempts at equating the aggressor and the victim, a thinly veiled criticism of Beijing’s stance. Such a communication strategy limits the scope for Beijing’s attempts to shape the narrative on EU-China exchanges.

- Testing offers: Close to two weeks after Li’s trip had finished, Wang Zichen, a Deputy Director of the China Center for Globalization (CCG), a think tank that often floats trial balloons of Chinese foreign policy ideas, suggested that China may be willing to play a more constructive role on Russia’s invasion under certain conditions. For instance, if the EU revitalizes the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, diverge with the US on restrictions of tech exports to China or withdraws from “US-initiated” restrictions on Huawei.

Quick take: The reactions to Li Hui’s visit draw a clear line – Beijing’s idea for “political settlement of the Ukraine crisis” that is rooted in relativizing the responsibility of Russia and ignores the UN charter has little appeal in Europe. But the EU needs to be cautious about Beijing’s upcoming offers like the one suggested by Wang.

Creating a clear precedence to decide on the fundamentals of international law on a basis of political or security concessions would be a very dangerous and questionable move. Regardless, it is unlikely that China would ultimately meaningfully shift its stance. Beijing is strategically linked with Moscow by its geopolitical considerations – namely, that the US is aiming to contain it and it needs partners, such as Russia, to push back. Tradeoffs such as CAI or tech access are not enough to make China re-evaluate its strategic priorities.

Read more:

- SCMP: Chinese envoy’s Europe trip a ‘search for common ground’ on Ukraine war, analysts say

- The New Statesman: Ambassador Fu Cong: “Europe will not become a vassal to China”

- MFA of the Republic of Poland: Deputy Minister Wojciech Gerwel met the Special Envoy of the Chinese Government for Eurasian Affairs

Short takes

Li Qiang’s Europe visit kicks off with German-Chinese government consultations

The seventh round of government consultations with the Chinese government will take place in Berlin on June 20 under the banner of "Gemeinsam nachhaltig Handeln” (Acting Sustainably Together). In an attempt to move away from "business as usual", there are signs that the German government wants the consultations to be comparatively low-key, with no major business deals concluded. In turn, Beijing wants the exchange to be high profile enough to signal that Germany remains China’s close economic partner and to emphasize its core interests, which largely revolve around gaining a strategic advantage in the power struggle with the US.

Despite German plans to separate business deals from the proceedings, the Chinese delegation, led by Premier Li Qiang, is scheduled to meet with members of the German business community before the official consultations. They will then head to Munich for further meetings with German business representatives before departing to France for a one-on-one between Li and President Macron.

- Politico: Germany mulls downsizing China summit

- Chinese Embassy in Berlin: Wang Yi trifft außen- und sicherheitspolitischen Berater des deutschen Bundeskanzlers

Joseph Wu’s Europe travel irks Chinese MFA

Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu addressed the European Values Summit 2023 on June 14. In his speech that followed the opening address by Czech President Petr Pavel, he asked for “support from European friends” to maintain the status quo. Wu is scheduled to visit Brussels for informal exchanges afterwards. The Chinese Foreign Ministry criticized the visit urging the European side not to support Taiwan “independence forces”.

- Reuters: China warns Europe against official ties with Taiwan ahead of minister's visit

- Focus Taiwan: Taiwan's foreign minister to visit Prague for summit speech

Portugal bans Chinese vendors from its 5G network

Portugal introduced a ban on companies from “high-risk” countries and jurisdictions preventing them from supplying 5G equipment for its telecommunication network in a decision that affects Chinese companies. According to the government’s Higher Council for Cyberspace Security, the “high-risk” category applies to all companies from non-EU, non-NATO and non-OECD countries. That includes Huawei, which has previously worked with some Portuguese telecoms companies to develop their 5G networks. China is reportedly planning a political response to the decision, using its influence in businesses like EPD, REN, Mota-Engil and BCP (bank).

- Bloomberg: Portugal Effectively Bans Chinese Companies From 5G Network

- Jornal de Negocios: Pequim admite retaliar chumbo da Huawei no 5G

Finland and US conclude their response to Chinese telecom technology

The two governments signed a Joint Statement on Cooperation in Advanced Wireless Communications, confirming their ambitions to cooperate in scientific research, standardization and technology development. Matti Latva-aho (University of Oulu, Finland) argues that the step comes in response to a debate in 2019 in which China indicated for which aspects 6G technology could be used, causing concerns among governments that what China envisioned was a police state. Finnish Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto stressed that because a 6G system could allow for misuse, the US and Finland want to see the technology used in a way that is “democratic, transparent and where human rights are respected.”

- Euractiv: Finland, US eye 6G to reduce Chinese tech dependence

- Helsingin Sanomat: Suomen ja Yhdysvaltojen 6G-yhteistyöllä varaudutaan myös Kiinan uhkaan

The Netherlands reviews Chinese chip acquisition under new investment screening law

The Dutch government is to examine the acquisition of Nowi, a Delft-based microchip startup, by Chinese owned company Nexperia. The law, which came into force in June, gives the government new powers to scrutinize investments or full takeovers when they involve critical infrastructure or sensitive technology.

In line with such tech and knowledge security concerns, the Dutch Education ministry also considers screening foreign students who plan to study in the technical fields for possible risks. One of several screening factors might be whether students receive high-profile scholarships by the Chinese government, as some Dutch universities already begun to reject Chinese students on this account.