Tech-driven growth takes priority over public welfare in China’s vision for development

At the National People’s Congress, Beijing pledged to ease the plight of workers and companies. But this talk of near-term reforms lacks substance, say Max J. Zenglein and Katja Drinhausen.

With the Chinese economy struggling, the 2024 National People’s Congress (NPC) seemed to offer glimpses of a leadership ready to correct course. Premier Li Qiang used his presentation of the government’s “work report” to the national legislature to promise to respond to the peoples’ “expectations” and “deepen reforms” in many areas. With a new Private Economy Promotion Law in the making, NPC member Lou Qinjian said “China’s door is always open to the world” and reiterated plans for an easing of foreign investment restrictions.

Beijing seems to understand that domestic and foreign confidence in China’s economy needs to improve as it grapples with major challenges – a downturn in the real-estate and stock markets, unemployment, stagnating incomes, social security gaps and local government debt. It reinforced the message of recent months that “reform and opening” are back on track – after years of an ideologically driven push to take stronger control over the economy – and set an ambitious economic growth target of “around 5 percent” for 2024.

But any hopes of a return to economic liberalization and market-oriented reforms would be misplaced. Xi Jinping places little trust in what used to be key success factors in China’s half century of reform and opening: citizens’ confidence and trust in the future, entrepreneurial spirit, foreign investment and collaboration. After years of regulatory campaigns to rein in the power of the private sector and the substantial cost of China’s rigid Zero-Covid policy, the economy is reeling amid sustained weak consumer and business sentiment. But the leadership seems to be treating these like minor hiccups that only distract from long-term strategic objectives.

Technological advancement and self-reliance remain front and center

“We must firmly grasp the primary task of high-quality development and develop new productive forces,” Xi told delegates. Giving Maoist terminology a new spin, the buzzword refers to innovation and high tech as the key growth drivers, a marked departure from Xi’s first term in 2013 nominally centered around improving market mechanisms. This stance does not bode well for meaningful changes in areas like social inequality, regional development, or a level playing field for domestic and foreign businesses. Companies in critical and emerging technologies will profit most from Xi’s ambitions, not traditional manufacturing and small enterprises that account for most job creation. Social policy goals take a backseat in the work report and with tighter government finances, it’s clear where priorities will lie.

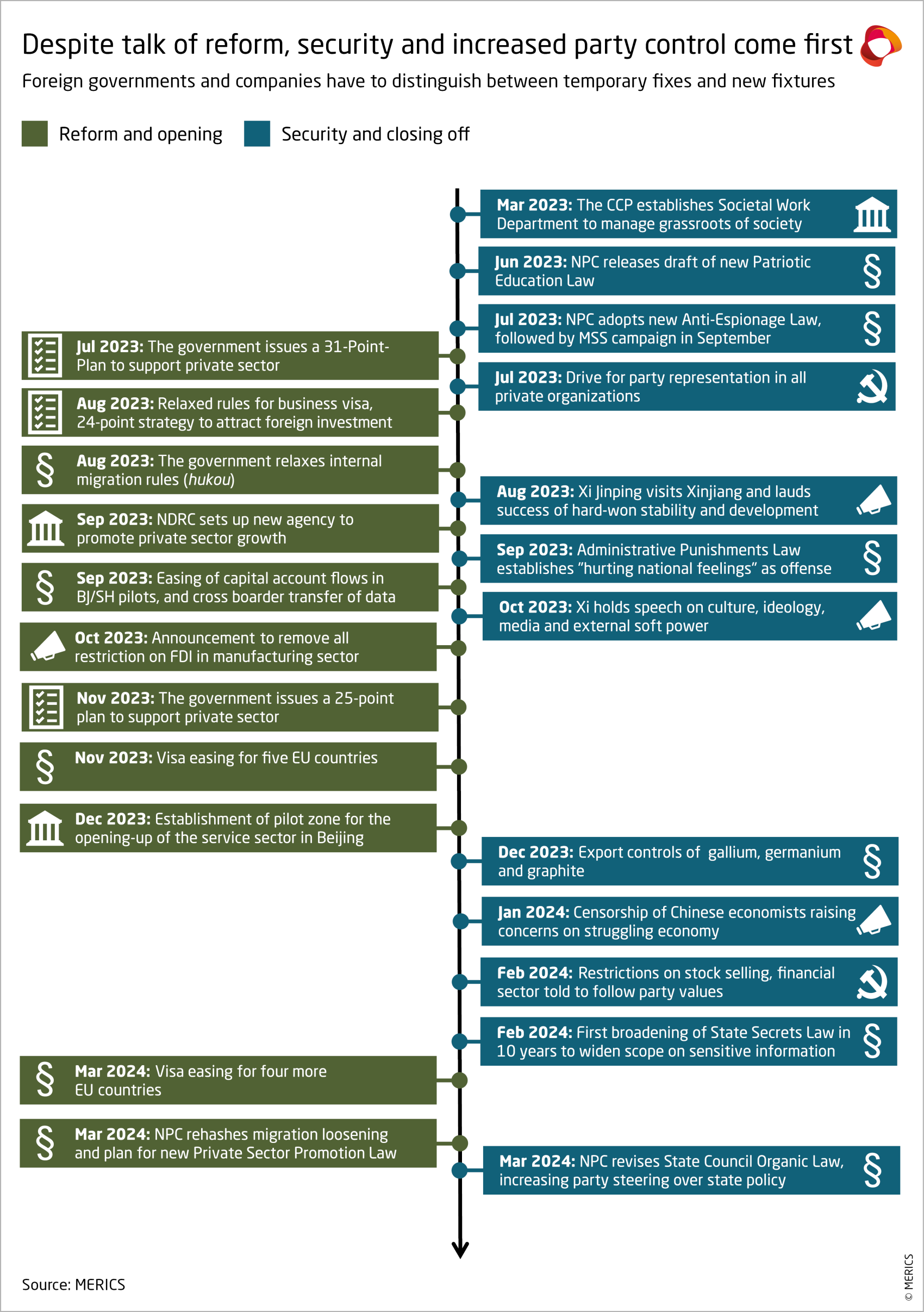

The Private Economy Promotion Law and other measures to help the private sector and foreign companies announced at the NPC offer little that has not already been tried. The central government has since mid-2023 announced plans promising equal market opportunities, access to finance and prompt invoice settling by public institutions. After foreign investment fell to a 30 year low in 2023, the government late last year relaxed capital account restrictions in Shanghai’s pilot free trade zone, rolled back restrictions on cross border data exports and relaxed visa rules. The measures have yet to produce a turnaround.

The main reason for this is the leadership’s continued emphasis on stronger steering by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and more technological self-reliance. Efforts to improve the business environment have come hand in hand with stronger party control, including a renewed push for party-cell building in the private sector, reports of volunteer militias set up in companies, as well as stronger guidance over what the party deems to be correct corporate behavior. Similarly, opening measures for foreign companies are also being undercut by moves in other areas. For example, the government plans to get rid of foreign equipment across its entire information infrastructure.

Ensuring China’s security is paramount for Xi. Just before the NPC, its Standing Committee adopted revisions to China’s State Secrets Law. Together with the revamped Anti-Espionage Law, it significantly expands the scope of what can be declared restricted information and espionage, making it more difficult to gather reliable information. The party’s grip on public opinion continues to tighten. A recent opinion poll showing public dissatisfaction with the current economic situation was swiftly censored, as were critical assessments of the country’s woes by well-known Chinese economists.

Beijing’s new development paradigm neglects an important part of the equation

The irony of China’s current weak economy is that it is inextricably tied to the leadership’s ambition of shifting the country to its vision of “quality growth”. Xi’s prioritization of manufacturing, tech and innovation capacity helps explain why the government induced the slowdown in non-strategic sectors like real estate. But the forceful and at times arbitrary implementation mean that the effects on large parts of society – the rise in unemployment, the decline of consumer and investor sentiment – were underestimated or – worse yet – treated as negligible.

The problem is that Xi’s economic vision is unlikely to shore up growth and restore public confidence any time soon – and may erode the existing base of domestic growth, if gains from the “new productive forces” fail to trickle down. China’s middle class is not in the mood to return to old spending patterns. Entrepreneurs, particularly in China’s small and medium sized companies, need to grapple with the stronger influence by the party and are wary about their place in China’s new development paradigm. It seems as if important parts of China’s economy are suffering from a form of “promise fatigue” well known to foreign companies.

Foreign governments and companies should take a cue from these domestic actors and distinguish between temporary fixes and permanent fixtures. The NPC’s political rhetoric can be read as a continued commitment to reform and opening. But a closer look at policy in the past year reveals that many are familiar and may be rolled back if the leadership changes its mind – unlike security-focused changes, made more permanent through legal and institutional changes. Xi’s “reform and opening” remain selective and conditional. International stakeholders should use the opportunities they offer, but not lose sight of underlying risks.