China’s vaccine diplomacy assumes geopolitical importance

Xi Jinping has pledged that a Covid-19 vaccine from China would be made a “global public good.” The larger Belt and Road Initiative, framed as a necessary component of the world’s post-corona economic recovery, is still relevant, but it’s the Health Silk Road that takes pride of place in China’s Covid-era diplomacy. This article is the first piece in a series on China’s international health politics. See also the second post on China's Health Silkroad and the third post on China’s efforts to pursue global health leadership.

On tour and in-country, Chinese diplomats are demonstrating Beijing’s beneficence by promising countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America preferential access to a Chinese vaccine.

Since Xi’s pledge in May, Beijing has added the words “at a fair and reasonable price” to its offer of a vaccine as global public good. As with everything else that Beijing promotes as a public good, including BRI projects, vaccine development will prioritize the interests of Chinese companies. Nevertheless, Beijing is better positioned than the US to assume global leadership in the march to vaccinate the world.

Contrary to Washington, Beijing has pledged to share vaccines

Unlike the US, China has joined COVAX – the vaccine partnership that aims to subsidize vaccine access for poorer countries and ensure equitable global distribution. Though Beijing must also find a balance between inoculating its 1.4 billion citizens and providing the vaccine as a “global public good,” China’s low caseload and manufacturing capacity mean it can afford to act more generously. And while it might be naïve to take Xi Jinping’s pledges at face value, Washington and Beijing have made very different statements on the issue of vaccine sharing. Instead of pledging access across developing countries, the US health secretary instead stressed that an American vaccine would only be shared once US needs have been met.

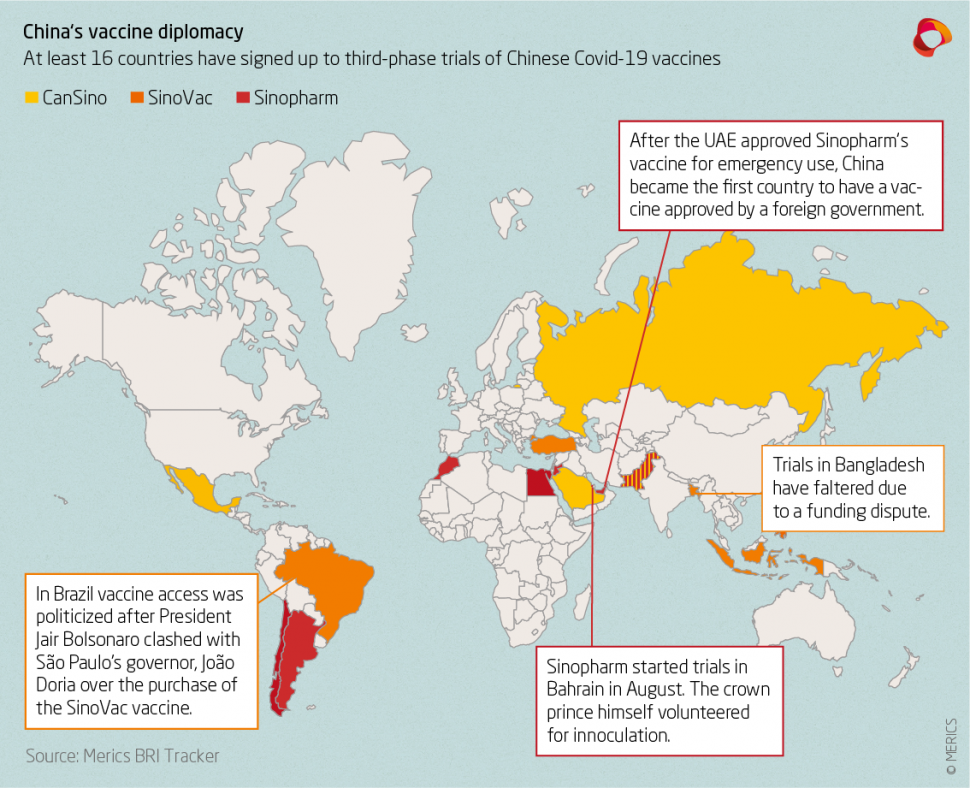

Earlier this month China’s party-state news agency Xinhua reported that China’s fifth vaccine candidate has entered the final, third phase of clinical trials. Due to a scarcity of homegrown coronavirus cases the Chinese vaccines are undergoing widespread third phase trials with partner institutions overseas, with at least 16 countries having signed up to trials so far.

China National Biotec Group (CNBG), a subsidiary of Sinopharm that is testing two inactivated vaccines, is conducting third phase trials in Argentina, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, Peru, and the UAE, where the crown prince himself volunteered for vaccination. Serbia was reported to have signed up to trials, but contradicting reports followed. Sinovac has enlisted Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Turkey, and the Phillipines, but trials in Bangladesh have faltered after a funding dispute. CanSino is or will be testing in Mexico, Pakistan, Russia, Saudia Arabia, and trials are pending approval in Chile. CanSino’s planned trial in Canada was scrapped in late August after Chinese officials allegedly held up shipments of the vaccine. Earlier this month it was reported that Uzbekistan is in negotiations with Sinopharm and has also offered to test a vaccine from Anhui Zhifei Longcom Biopharmaceutical, which is on the cusp of beginning third phase trials.

Countries hosting trials worked out agreements with China to purchase vaccine doses

Many of the countries hosting trials have also worked out agreements with their Chinese counterparts to purchase doses or manufacture the vaccine for local distribution – for instance, Indonesia will receive 50 million doses of concentrate from Sinovac for local production, while Turkey is set to purchase 20 million doses. In mid-September, the UAE even approved Sinopharm’s vaccine for emergency use, handing China the honor of being the first country to have a vaccine approved for use by a foreign country. Earlier this month Bahrain also approved Sinopharm’s vaccine for emergency use, and Indonesia is reported to be considering a similar decision regarding the late-stage Chinese vaccines.

Whoever wins the vaccine race, distribution will be political

If China becomes the first country to manufacture a safe and effective vaccine at scale, the achievement will carry symbolic weight, but the vaccine race may not have a clear-cut winner. After mixed results from CanSino trials in Indonesia and the great news on vaccine efficacy from Pfizer and Moderna, the narrative that China is winning the race has shifted. But a cost comparison between Pfizer’s new mRNA vaccine and more affordable Chinese alternatives suggests a more nuanced picture. Rich countries have been signing purchase agreements worth billions of dollars with Western vaccine producers, but China is still poised to supply the “developing world.”

In any event, the application of a Chinese vaccine will take on wider geopolitical significance. China has already offered USD 1 billion in loans to Latin America and the Caribbean for vaccine access, while Sino-Indian rivalry has found a new focal point around vaccine provision in Bangladesh. In Brazil, Chinese vaccine diplomacy has pitted Trumpish President Jair Bolsonaro against the governor of São Paulo, who wishes to purchase 46 million doses of the Sinovac vaccine.

Vaccine diplomacy is not without risks for Beijing. If China faces any of the same problems with its vaccines as it did with its faulty PPE, it could suffer serious reputational harm. Even if the vaccines perform well, unscrupulous Chinese individuals and companies might work in countries with poor institutional oversight to undermine the China brand. Beijing might also find itself exposed to an expectations gap between its rhetoric and what it can actually deliver.

The geopolitics of vaccine diplomacy is itself a risky business. In Southeast Asia there is already concern over the strategic costs of access to a Chinese vaccine. It is likely that Western commentators will echo flawed “debt diplomacy” arguments in accusing China of creating situations of dependency among its neighbors.

The Health Silk Road is will probably follow the Belt and Road in facing backlash and bumps along the way, but however it fares, we can expect the importance of “vaccine diplomacy” to overshadow that of Beijing’s former “mask diplomacy.”