China's new export control law

TOP STORY: New export controls give China new weapon in tech war

The facts: China’s top legislative body on October 17 passed the country’s first unified export control law. The adoption by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee enables the government to control the export of items including dual-use goods as well as military and nuclear products to specific foreign entities. Other goods, technologies and services – and related data such as technical information – will also be subject to controls, unless they were granted by export licenses issued by the State Council and Central Military Commission. The law, which took three years to draft and will come into effect on December 1, could also have an effect beyond China: both domestic and foreign companies can face criminal penalties if they violate the new rules. Crucially, the law seems almost intentionally vague in talking about safeguarding China’s national security “and interests.” This could allow Beijing to retaliate against countries or companies it deems as having broadly violated its export controls.

MERICS analysis: While China’s new law does not target any specific country, it almost certainly represents an effort to fight back against the United States’ ever-expanding export control regime, which has become a major headache for Chinese companies ranging from Huawei to semiconductor maker SMIC. In late August, China’s Ministry of Commerce already adjusted its catalogue of technologies subject to export controls to include artificial intelligence, opening up the possibility for the Chinese government to intervene in the upcoming forced sale of TikTok’s operations in the US. In the future, the existing control list could be expanded even further to enable Beijing to have a more direct say in the ongoing US-China tech conflict.

What to watch: It remains to be seen how China will make use of this new export control powers. The law at the very least acts as a show of strength that signals China will no longer stand idly by while other countries restrict the sale of technologies to Chinese companies. At the very worst it will give the Chinese government new means to punish the US and other countries, leaving their businesses caught in the crosshairs. Export controls could become a new flashpoint in EU-China relations and significantly impact European companies with extensive manufacturing and research and development (R&D) operations in China.

MERICS Executive Director Mikko Huotari said: “This is likely to create substantial challenges for European companies: the US, China and EU are all ramping up their export control regimes which will raise compliance costs and require a much more careful navigation of this new strategic landscape.”

Media coverage and sources:

- Reuters: China passes export-control law following U.S. moves

- Bloomberg: China Lawmakers Pass Export Control Law Protecting Tech

- Nikkei: China passes export control law with potential for rare-earths ban

- FAZ: China beschränkt den Export von Hightech-Gütern

- Politico: Europe to crack down on surveillance software exports

- NPC: Full text of Export Control Law

- MOFCOM: Aug 28 amendment of MOFCOM’s export control technology catalogue

- Xinhua: Official commentary explaining that ByteDance may need a license to sell TikTok in the US

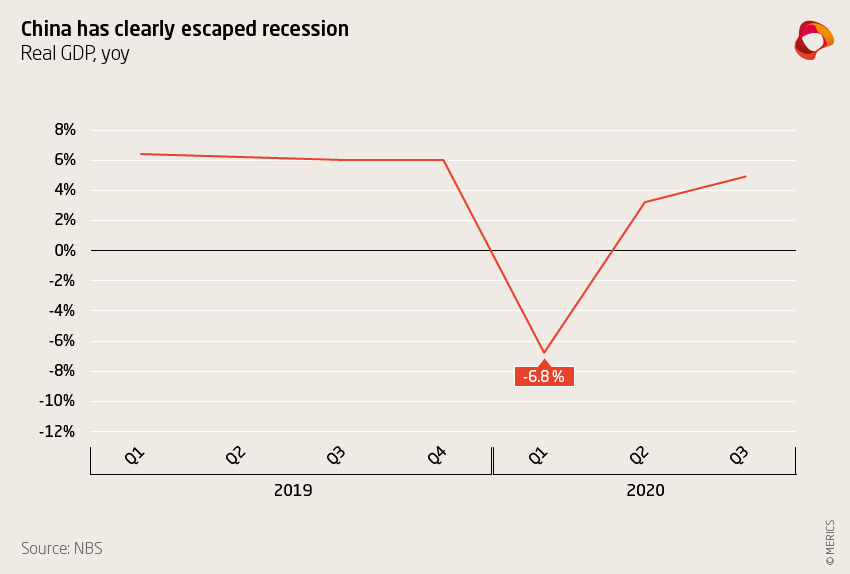

Crisis? What Crisis? China’s economy rebounds

The facts: China’s economy is showing clear signs of rebounding. The country’s gross domestic product rose 4.9 percent in the third quarter, setting it in stark contrast to the world’s other major economies which were all still in recession. Government stimulus measures – in the form of fiscal steps and looser credit conditions – boosted investment and led to it contributing the largest share of the growth. But domestic demand also recovered, with consumption contributing 1.7 percentage points to growth. Exports also contributed thanks to resilient global demand that meant shipments abroad were nine percent up on the third quarter of 2019. While imports lagged, they began a strong rebound in September that suggests that demand – which grew 13.8 percent in September – is coming back.

What to watch for: China’s economy is performing better than others in the rest of the world, but there are risks. Credit conditions were an issue before the pandemic and have only worsened since. China’s largest property developer, Evergrande, is already struggling under an enormous debt burden – and there will likely be more cases like this in the future.

MERICS analysis: Beijing’s effective containment of its Covid-19 epidemic, quick stimulus measures and external demand are key factors in China’s economic recovery. Stimulus measures are likely to stay in place until household consumption and the labor market are on a more solid footing. Barring a second wave, China’s economic recovery is well on track.

"The Chinese government has mastered the Corona crisis fairly well so far, and has limited economic damage, especially for the middle class. But, if economic recovery fails to materialize in its major foreign markets, China's exports will most likely suffer setbacks," says MERICS Chief Economist Max J. Zenglein.

More on the topic: The next issue of the MERICS Economic Indicators, our quarterly analysis of China’s economy, will be published this Friday, October 23, 2020. Stay tuned.

Media coverage and sources:

- National Bureau of Statstics: Economic data for Q3/2020

- AP: China’s economic recovery accelerates

New EU screening framework also targeting Chinese FDI is finally in place

The facts: One and a half years after European member states approved it, the EU framework for screening foreign direct investment (FDI) finally became operational on October 11. It provides the EU Commission and member states with a mechanism to exchange information about investment projects by third country investors. The Commission can now issue an opinion if it sees an investment posing a threat to the security or public order of more than one member state. The tool targets all investments into sensitive areas of the economy, which have been increasing during the last decade.

What to watch: Brussels has more proposals in its pipeline that could strain relations with China. For example, it is finalizing plans to tighten export controls on technology used for espionage and surveillance. It is also working on an ‘anti-coercion’ mechanism to use against trade bullies and new standards for ‘greener’ car-battery imports, a sector dominated by Chinese manufacturers. On the political stage, Brussels has put forward a proposal on sanctions for human rights violations – a step that might concern Beijing in light of the EU’s criticism of China’s actions in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

MERICS analysis: "The new tools and proposals show that the EU’s China policy is becoming truly multifaceted to address the many challenges that are part of the EU’s relations with China. FDI screening and anti-coercion tools can serve Brussels in defending Europe’s strategic autonomy and economic sovereignty. Better export controls and a human rights sanctions regime would allow the EU to act in line with its values,” says MERICS expert Lucrezia Poggetti.

Media coverage and sources:

- EU Commission: EU FDI screening regulation enters into force

- Politico: Europe to crack down on surveillance software exports

- EU Commission: Towards a European framework to address human rights violations

- Euractiv : Dombrovskis announces defense instrument against trade bullies

- Euractiv : EU pushes new standards for ‘greenest’ car batteries on earth

Modern Shenzhen turns 40 and becomes focus for Xi’s tech ambitions

The facts: Shenzhen in mid-October gave CNY 10 million of China’s new digital currency (DCEP) to 50,000 citizens through a citywide lottery, making it the fourth Chinese city to trial the virtual currency. The rollout is the largest to date and came amid celebrations marking the 40th anniversary of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) on 12 October. President Xi Jinping arrived in Guangdong province that day for a 3-day tour. He attended a ceremony in Shenzhen celebrating the establishment of the city as Special Economic Zone, a move spearheaded by his father, Xi Zhongxun, then Party Secretary of Guangdong Province. Xi praised Shenzhen's development and stressed the need to drive reform and opening up, innovation and development. His visit came shortly after the release of a five-year development plan for Shenzhen that includes data trading, wider market access and digital currency, bolstering the city’s position next to Hong Kong and as China’s equivalent of Silicon Valley.

What to watch: “Indigenous innovation” and “self-sufficiency” have been prominent terms on China’s political agenda, especially under Xi. His renewed emphasis of both ideas while in Shenzhen and the massive distribution of DCEP to the city’s citizens couldn’t be more symbolic of its status even as neighboring Hong Kong sets about redefining its financial and economic role. But the actual impact of the new reform plans and the virtual currency could prove slight. The plans as yet set few concrete goals and it could yet prove tough to establish a new digital currency – especially as Wechatpay and Alipay already dominate the markets for digital payments that they created in the last few years.

MERICS analysis: With the 14th five-year plan in the last drafting stages and ever more issues causing tensions in external relations, Xi's ambitions for Shenzhen show the urgency of China’s quest for technological innovation. The issue will likely receive even more attention than before. While Xi’s speech was short on concrete details, driving indigenous innovation, technological self-reliance, as well as continuation of a state-driven and controlled development of markets are clearly becoming a top priority for China's leadership. Announcing continued opening and development of financial markets and technology, including digital currency, is also aimed at attracting talent and shifting investments from Hong Kong, eventually integrating the two systems further into one country.

Media coverage and sources:

METRIX

139 countries have supported China’s election to the UN Human Rights council. That is 41 less than in the previous election and the weakest result since the council was founded in 2006. All 193 UN member states can vote for the 15 vacant seats in the council, which are distributed among five regions. The results indicate that Beijing’s global reputation is suffering from the crackdown on Hong Kong and human rights violations in Xinjiang as well as its behavior abroad (Source: Quartz)

REVIEW

“Charity with Chinese Characteristics” by Katja Levy and Knut Benjamin Pissler (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020)

Non-governmental organizations (NGO) founded by Chinese tech and industry giants such as Tencent and Alibaba have donated millions of masks, test kits and other medical equipment since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. The important role charitable foundations play in China’s recent “health diplomacy” may surprise non-experts familiar only with China’s state-centered system. As in other countries, civil society has become a factor in China – and the actors have changed fundamentally since state-led organizations first took the stage in the 1980s. Private foundations and their sponsors play an ever more important role in and outside the country. Yet their role is poorly understood.

This book explores China’s charitable foundations and the space they have carved out for themselves. The 7,000 officially registered foundations only make up a fraction of the roughly 810,000 registered social organizations. The book focuses on this small set of organizations, but still manages to give insights vital to understanding the development of civil society in China as a whole. Both authors have worked extensively on this topic and skillfully combine interviews with practitioners working in the field with more technical analyses of the legal and political framework within which NGOs operate.

Parts of the book might appeal more to fellow researchers – they include an extensive review of literature, a thorough historical background and a description of different theoretical approaches to civil society. But interested readers and people who deal with Chinese organizations regularly will also profit from this study and appreciate how the party-state views NGOs and is integrating them further into its agenda and legitimacy narrative. They will see how the state wants to steer actions by defining preferred areas of action, mandating supervision by state organizations, establishing party cells and party members in key positions. But also how China’s new stakeholders have a sense of agency and professionalism that defines their scope of action as they chart their course.

Review by Senior Analyst, Katja Drinhausen

VIS-À-VIS: Plamen Tonchev: “Apart from ‘greening’ the BRI, Beijing is called upon to demonstrate it can also ‘clean' it from excessive financial burden.”

MERICS China Briefing spoke with Plamen Tonchev, Head of Asia Unit at the Institute of International Economic Relations (IIER), Greece. As a MERICS European China Policy Fellow, he is studying China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) global infrastructure scheme and its impact on climate change.

Questions by Gerrit Wiesmann, freelance editor

Chinese President Xi Jinping recently pledged China would be carbon neutral by 2060. How big a part does BRI play in his ambition?

Xi’s pronouncement at the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly cuts both ways. Firstly, he pledged China would scale up its goals under the Paris Agreement, the so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), and aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. The fact that China has set time-bound milestones is deemed a largely positive development. To what extent they will be met remains to be seen – they are a goal, not a given.

What is certain at present is that China’s greenhouse gas emissions will keep rising for at least another decade. This does not sound reassuring to me – it certainly doesn’t seem to demonstrate a sense of urgency about combatting climate change. Secondly, while Chinese authorities state they are trying to address domestic pollution, China’s rust-belt industry has been busy along BRI routes – a number of coal-fired power plants are being built in Asia, Africa and Southeastern Europe. In reality, while aiming to improve at home, China is exporting carbon-intensive economic activities abroad and placing the burden of CO2 emissions on other countries’ shoulders.

Indeed, China has funneled a large chunk of BRI funding into coal projects. But it is also talking about “greening and cleaning” the BRI...

Again, these are pronouncements, words that need to translate into deeds. True, at the second Belt and Road Forum in April 2019 Xi spoke about an “open, green and clean” BRI. It is widely seen that Beijing’s new rhetoric is an acknowledgement of controversies surrounding many China-funded infrastructure projects, including those with a big carbon footprint. China now needs to prove in practice that it is as good as its word. Interestingly, any trend towards financing less carbon-intensive projects might have more to do with Covid-19 than with Beijing’s commitment to “greening and cleaning” BRI. Rising debt and insolvency risk in a number of recipient countries has made China’s policy banks, the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, more cautious about lending to the kind of large-scale infrastructure projects that normally contribute to CO2 emissions.

To what extent is “greening the BRI” driven by the search for new renewable-energy markets? And what does this mean for Europe and the US?

Over the past decade, China has seen a boom in renewable energy sources, mostly photovoltaics (PV) and wind. This is a key part of the government’s low-carbon strategy, which is based on considerable state aid in the form of guaranteed electricity prices. For instance, between 2010 and 2017 China’s installed PV capacity soared from 40 GW to 250 GW, twice as much as in the rest of the world. This hit the global market, driving a number of European and American panel producers out of business.

But this breakneck growth in China led to an unsustainable cost of state aid and a high risk of overcapacity. So, two years ago, the government abruptly changed course and slashed subsidies for solar panel producers. This was announced in mid-2018, on May 31, hence the policy’s name, “531”. Chinese solar panel producers are now desperate to clinch contracts abroad – and this is where the BRI comes in handy for Beijing.

PROFILE: Who’s afraid of Genghis Khan, former Great Khan and Emperor of the Mongol Empire?

Who’s afraid of Genghis Khan, former Great Khan and Emperor of the Mongol Empire?

A museum in the French town of Nantes has put the legendary Mongolian ruler – immortalized in countless old films and as a hard-drinking, womanizing warrior in a 1979 German Schlager song – back into the public eye. The history museum had conceived a Genghis Khan exhibition in cooperation with the Museum of Inner Mongolia in Hohot, only to suddenly shelve it. According to the museum, the Chinese government’s heritage officials urged it to drop the name "Genghis Khan" from the exhibition’s title and also suggested terms like "empire" and "Mongolian" were not acceptable.

Genghis Khan (Chinese: Chengjisihan 成吉思汗) was born around 1160 and originally called Temüjin (blacksmith). His life produced a litany of myths and legends: a slave in stretches of childhood and youth, a commander as successful as cruel, a father to countless children. The Great Khan and his successors built an empire that at its height encompassed 25 million square kilometers – and for more than a century, parts of today’s China were part of it. With his campaigns of conquest, Genghis Khan laid the foundations for the first foreign-led regime in ancient China, the Yuan Dynasty (1279 - 1368).

Modern China's attitude towards Genghis Khan has always been ambivalent. In a poem, Mao Zedong once praised him as the "proud son of heaven", appropriating him for Chinese culture. More recently, nationalist Han Chinese have questioned such approaches and, for one, boycotted a 2018 film that in their view lionized Khan too much. Genghis Khan would probably not like Beijing's current policy towards Mongolians any more than the six million strong minority does. Mongolians protested this summer when Beijing said some schooling in Inner Mongolia would be held only in Chinese.

Given what Bertrant Guillet, the director of the museum in Nantes, reported about the exhibition’s preparations, Beijing seems to think it unwise to give Genghis Khan too much visibility as a Mongolian warlord. Guillet clearly distanced himself from what he called Chinese "censorship". He described how Chinese officials had tried to control the content of brochures and the wordings on displays and maps, and sought to reinterpret facets of Mongolian culture "in the spirit of a new national historiography”. As a result, the exhibition will now take place in 2024, probably without exhibits from China. The old fear of the all-conquering Genghis Khan – it seems to be alive and well today in Beijing.

By Claudia Wessling, Director Publications, MERICS

MERICS China Digest

MERICS’ top 3

- Financial Times: Ant Group under scrutiny over exclusive sale of shares in IPO

- ASPI: The flipside of China’s digital currency

- The Guardian: Member of Taiwanese delegation to Fiji assaulted by PRC diplomats

International relations:

- Wall Street Journal: China warns US it may detain Americans in response to prosecutions of Chinese scholars

- The Diplomat: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi concludes five-day tour of Southeast Asia

- Helsinki Times: Finland suspends extraditions to Hong Kong

- South China Morning Post: Cyprus scraps "golden passport" scheme that granted citizenship to rich Chinese investors

Politics and society:

- The Atlantic: How milk tea became an anti-China symbol

- BBC: Missing Hong Kong protester Alexandra Wong says she was held in mainland China

- New party directive issued on operation of the Central Committee

Economy, finance and technology: