MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker 02/2023

Focus topic

The geopolitics of China’s mediation push

by Helena Legarda

China has positioned itself as a potentially credible international mediator by brokering the recent agreement for Saudi Arabia and Iran to restore their diplomatic relations.1 It was only one of several such moves by Beijing over the last few weeks: China has offered to mediate in the Israel-Palestine conflict and reemphasized its wish to facilitate talks between Russia and Ukraine.2 Beijing has also set up an International Mediation Organization in Hong Kong.

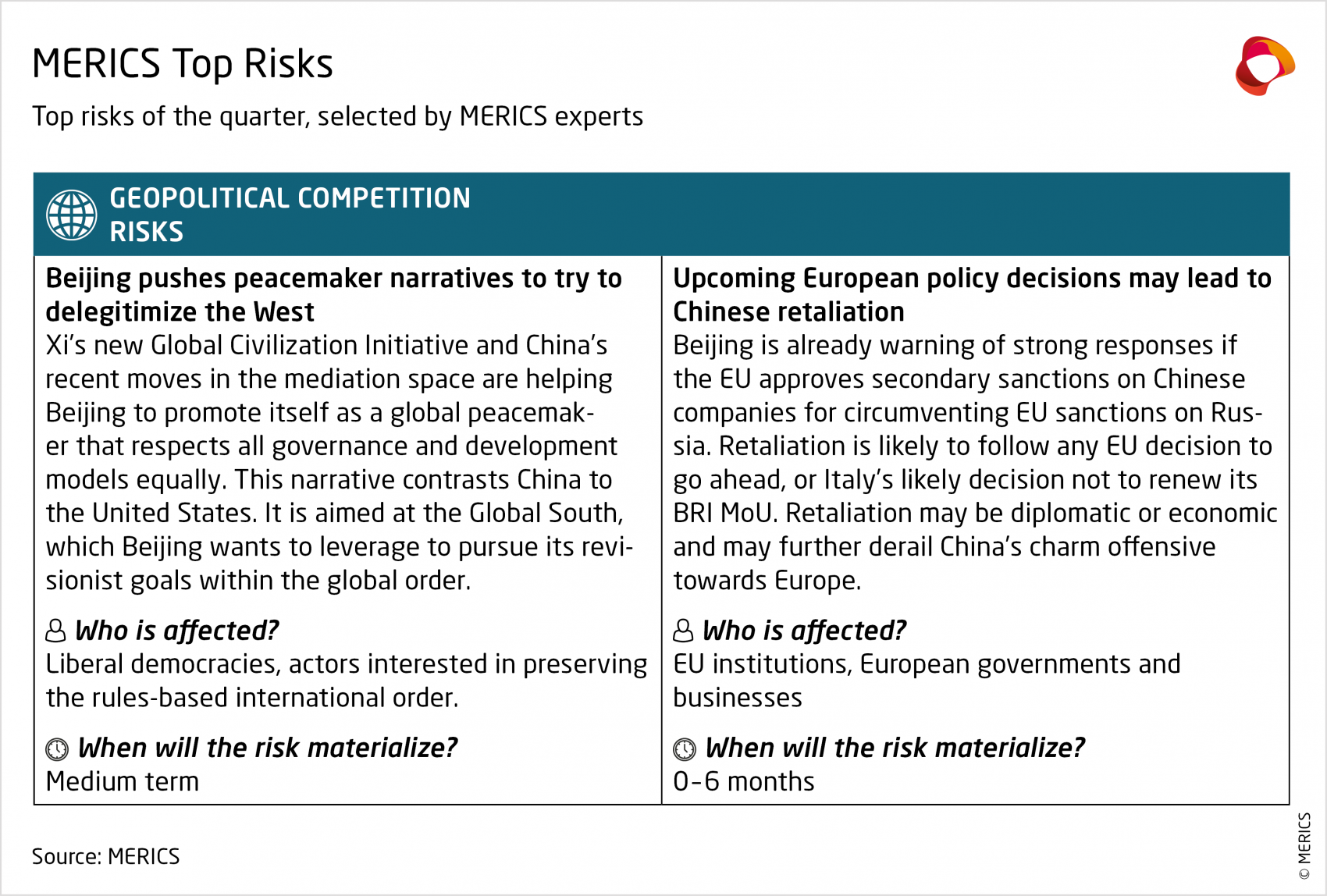

China is pushing its self-image as a peacemaker and a responsible global power. Beijing's recent moves may signal greater willingness to get involved in international mediation processes. However, European actors should be cautious about Beijing’s motivations and the likelihood it will take on sufficient responsibility or deliver outcomes. China’s current mediation push seems to be largely a reflection of its geopolitical competition with the United States and its ambition to expand its global influence at the expense of the West.3

China plays a greater role in international mediation, but with limited success

China is certainly playing a bigger role in foreign conflict mediation than ever before, but for now, its role remains limited and, in most cases, non-decisive.

Since 2018, Beijing has mediated or participated in multilateral conflict resolution efforts in at least four conflicts and has offered to mediate or facilitate talks in another four - a clear sign of its growing ambitions and involvement.4 From Afghanistan and Yemen to the Bangladesh-Myanmar conflict or the Horn of Africa, Beijing’s approach focuses mainly on high-profile mediation tools targeting top levels of government. These include host diplomacy (inviting the leaders of both sides to Beijing) and top-level visits by Chinese officials.

Although China claims to be a full mediator, its role has mostly been limited to dialogue facilitation. So far, the Chinese leadership has been reluctant to make concrete, original proposals for peace agreements in any of the conflicts it has become involved with. It has also held back from providing incentives that might encourage concessions, or from applying pressure when negotiations encounter obstacles.

Beijing’s role is still characterized by its late-stage involvement, its unwillingness to lead the process alone, and by grand gestures or offers with little concrete follow-up. Beijing’s offers are often made without prior consultation with all the conflict parties. China’s role in the successful reestablishment of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, for example, saw Beijing coming into the process at the very end, once it was clear that an agreement was possible. Prior to this, mediation had been conducted by other regional powers, including Iraq and Oman.5 Beijing’s involvement was probably not the only deciding factor, even if it did bring the process to completion. But arriving at a late stage in the process enabled Beijing to claim responsibility for sealing the deal.

An additional obstacle to Beijing’s ambitions is that China's mediation approach tends to not follow international best practices: it often disregards concepts such as consent, impartiality, inclusivity and national ownership. Beijing often openly takes sides, making it difficult for all parties to accept its arbitration. In the conflict between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, China backed Addis Ababa.6 Its stance towards the Ukraine war remains largely pro-Russian. Beijing’s 12-point position paper on the Ukraine crisis was issued after more than a year without any contact between Ukraine and China’s leaders.7 It was most likely drawn up in coordination only with Russia.

Beijing shows a clear ambition to get more involved in conflict resolution efforts and to be perceived internationally as a peacemaker, but also a degree of unwillingness – or inability – to overexpose itself to the risk of negotiations breaking down, or to enforce agreements once they are concluded.

Beijing’s mediation push is driven by geopolitical competition

China’s mediation ambitions go back to the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. Beijing’s increased involvement in international conflict resolution was initially driven mostly by economic interests – which require stability in key regions – and its desire to project a positive international image.8

The economic rationale remains in place. Many of the conflicts that Beijing is mediating, or has offered to mediate, are in countries or regions along the BRI where it has economic interests. Both Iran and Saudi Arabia, for example, are key oil suppliers China needs to meet its growing energy needs. Instability in Afghanistan or Myanmar could affect key BRI corridors. And the Horn of Africa hosts China’s first and only overseas naval base in Djibouti and sits on a global shipping route. Hundreds of Chinese companies operate in the region.

But Beijing’s most recent moves seem more driven by geopolitical dynamics. Establishing itself as a global mediator is part of the application of the Global Security Initiative (GSI) that President Xi Jinping launched in 2022.9 Beijing presents the GSI as a “Chinese solution to international security challenges” that is meant to lay the foundation for an alternative global security architecture. Tapping into global dissatisfaction with the continuing war in Ukraine, Beijing uses the GSI to present itself as a peaceful country that prioritizes dialogue and is a force for stability. Beijing’s official narrative contrasts its stance with the United States and other Western countries that, it says, provoked the conflict and are still “adding fuel to the fire”.

A more active role in conflict resolution could help Beijing promote this narrative and pursue three key objectives: (1) cultivate its own image as a peacemaker; (2) delegitimize the United States and other Western countries; (3) expand its influence across the Global South to build an alternative coalition of countries.

China’s decision to establish a new International Organization for Mediation (IOM) headquartered in Hong Kong shows how these three objectives interlink. Run by Beijing, the organization is built on Chinese concepts and principles, such as “mutual respect” or “win-win cooperation”. Its declared goal is to settle international disputes by peaceful means in order to “promote world peace, security and development”. Claiming leadership in these efforts will allow Beijing to burnish its own image.

China is not the only country involved in the IOM. The joint declaration on the body’s establishment included other signatories, such as Indonesia, Pakistan, Cambodia, Belarus or Algeria.10 The details of their involvement, or of the IOM’s projects and functioning, are still unclear. But for now, their diplomatic support indicates Beijing’s coalition building efforts are proving partially successful and gives China an opportunity to cultivate an alternative institution and approach to mediation.

Opportunities for cooperation may emerge, but caution is required

Although Beijing's involvement in foreign conflicts is largely interest-driven, its new mediation push may still be a positive development that creates opportunities for cooperation with Europe. Sino-European interests can overlap when it comes to finding ways to manage and stabilize ongoing conflicts around the world. Sustainable peace agreements would be welcome in any of these conflicts, regardless of who brokers the peace. European actors should try to engage with China’s efforts where these seem serious and productive.

However, a degree of caution is necessary. The geopolitical drivers behind China’s ambitions, together with Beijing’s approach to mediation, will create challenges for any potential cooperation. China’s policy of stepping into mediation processes late and its reluctance to accept the risks of leadership in conflict resolution processes could make Beijing an unreliable mediation partner or even a free-rider - seeking mainly to claim credit for any successful outcomes.

The links between China’s conflict resolution activities and the GSI may also create situations that require proactive pushback – for instance if Beijing were to promote narratives, norms and values that clash with European ones. As Beijing’s primary focus is its competition with the United States, this may well hinder cooperation with countries seen as too close to Washington – a label that could apply to many European nations.

China will continue to take on a more active role in conflict mediation in the future. It will present itself as a neutral party that works with countries regardless of their political systems, and does not impose any requirements or preconditions ahead of negotiations. Beijing will leverage the GSI and China’s lack of historical baggage in many key regions of the world to depict itself as a more reliable partner than the United States or other Western countries, thereby expanding its global clout. However, European actors should remain realistic about the chances of successful Chinese mediation. Beijing remains a risk-averse actor, unwilling to take responsibility or act as a guarantor for a deal. Building alignment among EU member states on how Europe should respond to potential new mediation initiatives by China should be a priority, lest Beijing uses its offers to weaken European alignment.

Key developments of the quarter

Domestic stability

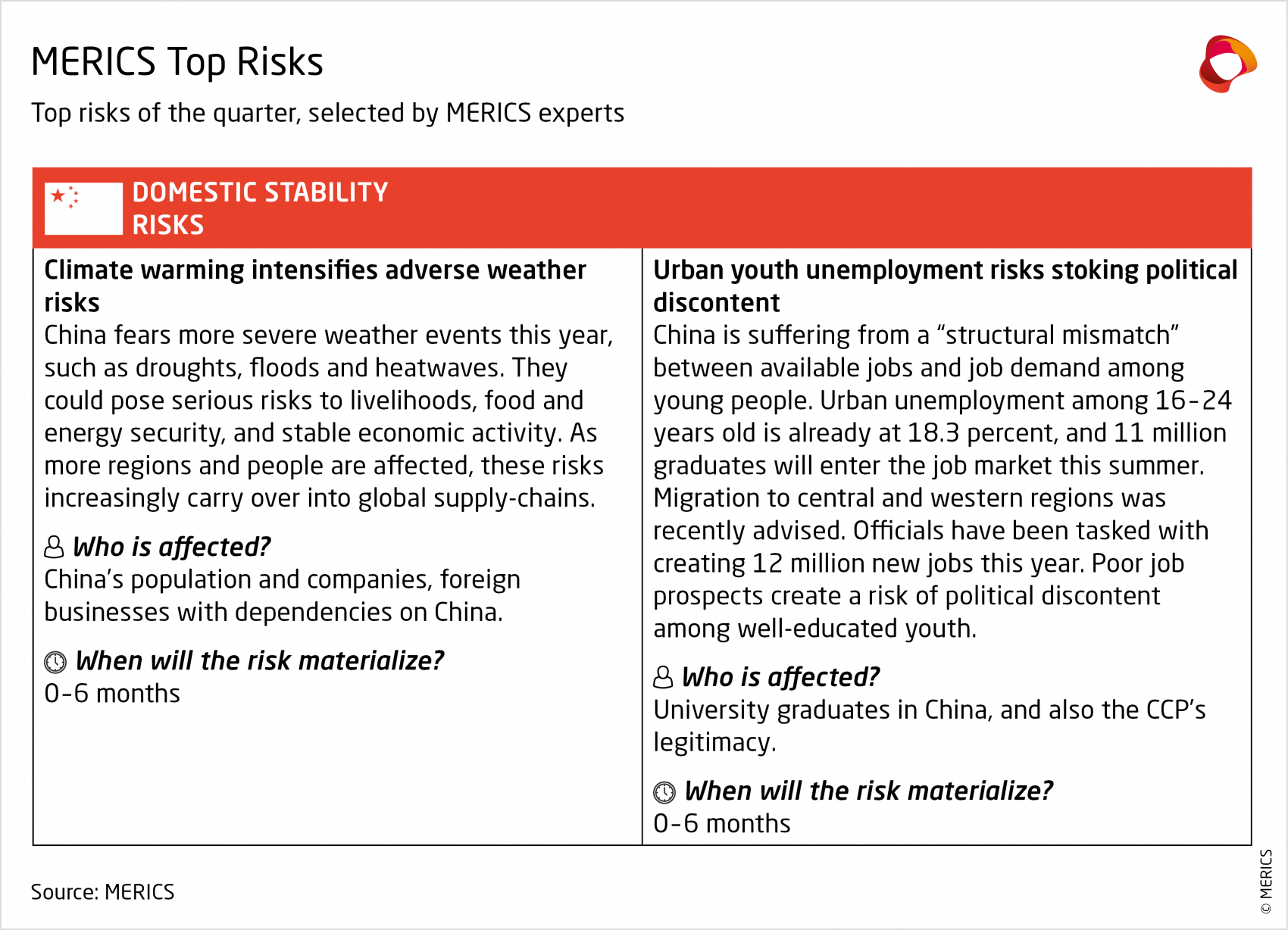

Rising socio-economic stress challenges China’s authorities

In the aftermath of Beijing’s strict zero-Covid policy, Chinese citizens are trying to recoup their losses and get back to normal. But the last three years have left marks in the socio-economic fabric of the country and exacerbated structural challenges. Economic growth is unlikely to rebound to former levels, and local government coffers have been drained by costly zero-Covid measures. Record youth unemployment, rising inequality, and sluggish household income growth all present the leadership with tough challenges.

After declaring the successful eradication of extreme poverty in 2021, any visible backsliding would amount to failure for Xi’s vision of “Common Prosperity”. There is evidence that discussions of Covid-related policy failures and poverty have been censored online.

Officials acknowledge that stabilizing the labor market remains the most difficult task for this year. To achieve the newly coined “high-quality development”, they must invest more in upgrading blue collar workers’ skills and expanding labor and health safety nets. As a quick fix, the leadership is contemplating a “mobilization plan” to divert hundreds of thousands of unemployed youth to rural and less developed Western regions in order to absorb the millions of new job market entries.

China has also reported a population decline for the first time. It needs to face the looming issues of an aging population. Still lacking adequate health care and pension systems, Beijing fears China is “getting old before getting rich”. Rural and less developed areas are particularly likely to experience gaps in care and coverage. Forceful structural reforms to push wealth redistribution have not yet materialized, so inequality may reemerge as a source of tension between the government and its citizens.

The leadership seems to be concerned about rising socio-economic stress. After the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March, the CCP established a new Central Department for Societal Work to better monitor and manage social risks. It is meant to improve top-down guidance on how to deal with petitions from disgruntled citizens, ease social tensions and ensure the stability of private small and medium size businesses.

Security and defense

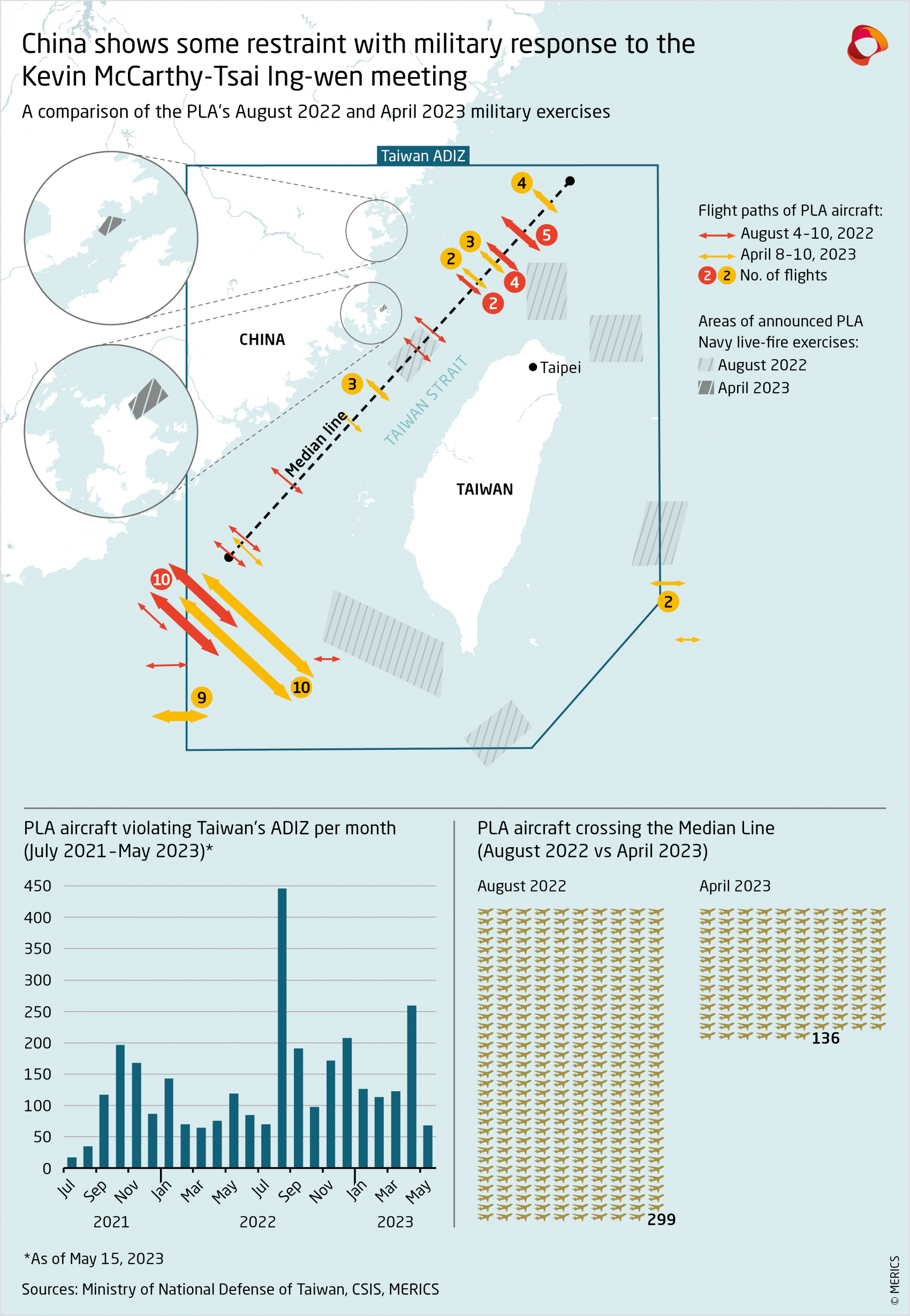

Beijing shows restraint ahead of Taiwanese presidential elections

In early April, Beijing once again unleashed large-scale military exercises after a meeting between Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen and the US House Speaker. Beijing’s more aggressive posture in the region has become the new normal. However, the exercises were limited in scope, which suggests a new awareness that the risk of escalation in the Taiwan Strait is becoming all too real and measures should be taken to keep the situation from getting out of control.

The approaching January 2024 presidential elections in Taiwan may have played a role in Beijing’s calculations too. The KMT party is Beijing’s preferred interlocutor in Taiwan. An overly aggressive military response might worsen the KMT’s chances of winning power. Beijing may also be leaving itself room to escalate its response after the elections.

Tsai’s meeting with new US House Speaker Kevin McCarthy took place on April 5 in California, as she “transited” through the United States on the way to Belize and Guatemala. The pair met on US soil rather than in Taiwan to avoid provoking Beijing but the Chinese leadership still threatened “resolute countermeasures”.

However, Beijing’s reaction was more moderate than expected. The military exercises were shorter in duration, and smaller in scope and scale than last August’s. The PLA operated further away from Taiwan this time, and no missile launches took place. Beijing quickly backtracked on the initial announcement it would impose a 3-day no-fly zone north of Taiwan, reducing the duration to only 27 minutes. All these moves signal a degree of restraint on Beijing’s part, though it does not make these exercises any less significant in terms of military training and preparedness.

Tensions will remain high in the run-up to the January 2024 elections, but Beijing may show some restraint to avoid a worsening of the situation. This will be even more important as Beijing and Washington are currently quietly laying the groundwork for their bilateral diplomatic reengagement through a series of high-level meetings – for instance, the one between top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi and US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in Vienna.

Geopolitical competition

Beijing reconnects with Ukraine without distancing itself from Russia

The long-awaited call between presidents Xi and Volodymyr Zelensky finally took place on April 26. The conversation, which Zelensky described as “meaningful”, marked the first direct contact between the two heads of state since Russia invaded Ukraine 14 months earlier. Diplomatic reengagement is a positive development, but it does not signal any change in China’s position on the war. Beijing has also used the last few weeks to reemphasize its close partnership with Russia.

As Xi made clear during his visit to Moscow in late March, Sino-Russian relations are as strong as ever. He described the two countries as drivers of geopolitical “changes unseen in a century”, a message reiterated by China’s new defense minister Li Shangfu during his own meeting with President Vladimir Putin a few weeks later. China also remains one of Russia’s economic lifelines amid mounting Western sanctions, and there is evidence that Chinese tech and dual-use components are being used by Russian troops in Ukraine.

Beijing’s position on the war does not seem to have changed, and neither has its support for Russia or its view of the United States and NATO as instigators of the conflict. During the call, Xi’s comments were consistent with China’s longstanding position. He refused to name Russia as the aggressor and did not acknowledge any pre-conditions for talks to begin (such as the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory). He called for the “restoration of peace” and announced China’s Special Representative on Eurasian Affairs Li Hui would travel to Ukraine. Li’s visit to Kyiv and other European capitals made clear that a constructive role by Beijing would be welcomed, but peace talks can only take place on Ukraine’s terms, nor Russia’s.

The call was most likely an attempt by Beijing to burnish its image and credentials as a peacemaker, in opposition to the United States and other Western countries. It may also have been timed at least partly as a way to appease anger in European capitals after China’s ambassador to Paris, Lu Shaye, questioned the sovereignty of ex-Soviet republics in a media interview. Even if the call was only a symbolic step, it was an important one to reestablish direct contact between the two capitals. It also provided Kyiv with an opportunity to clarify its positions regarding any potential negotiation with Moscow.

Economic and tech security

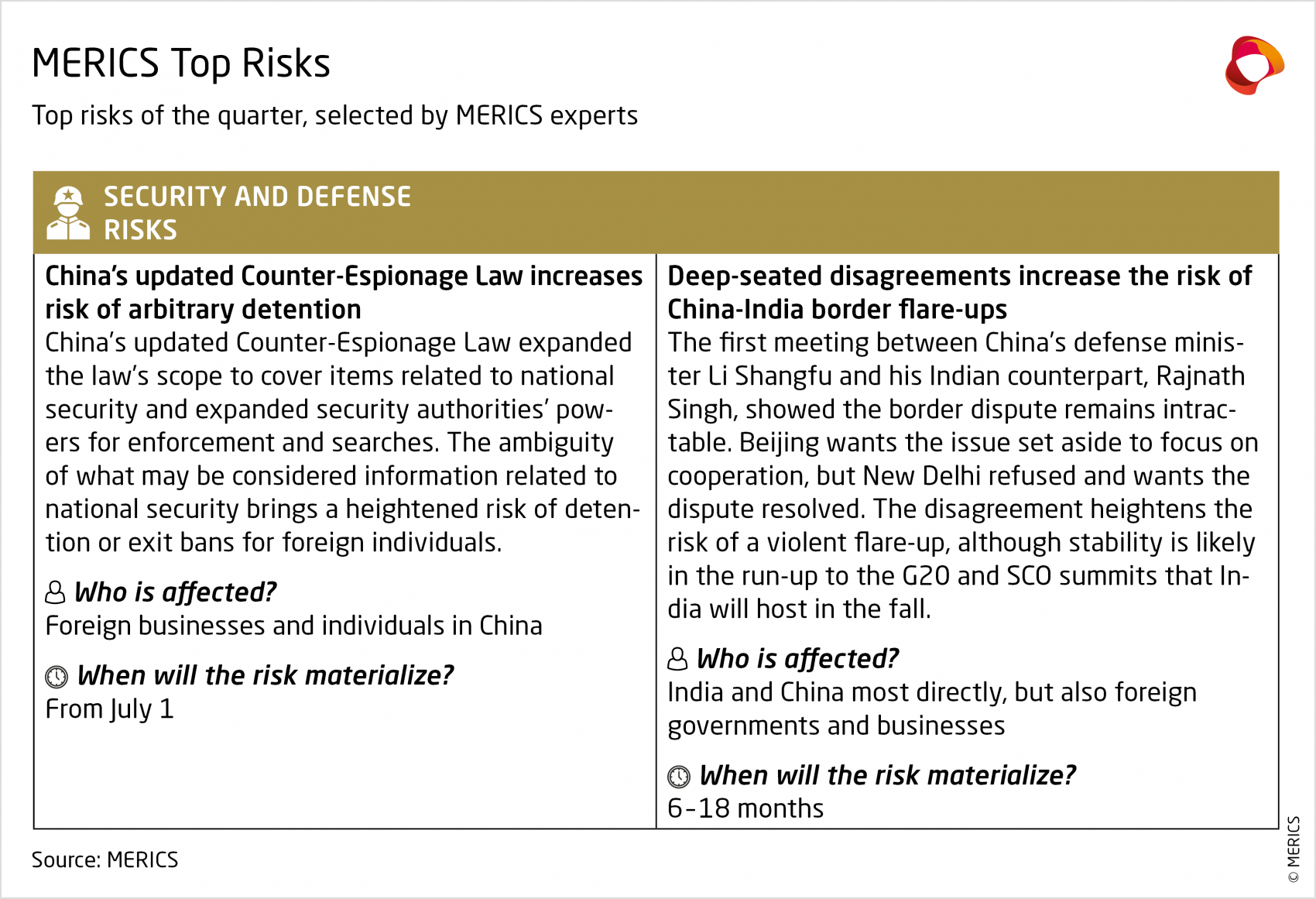

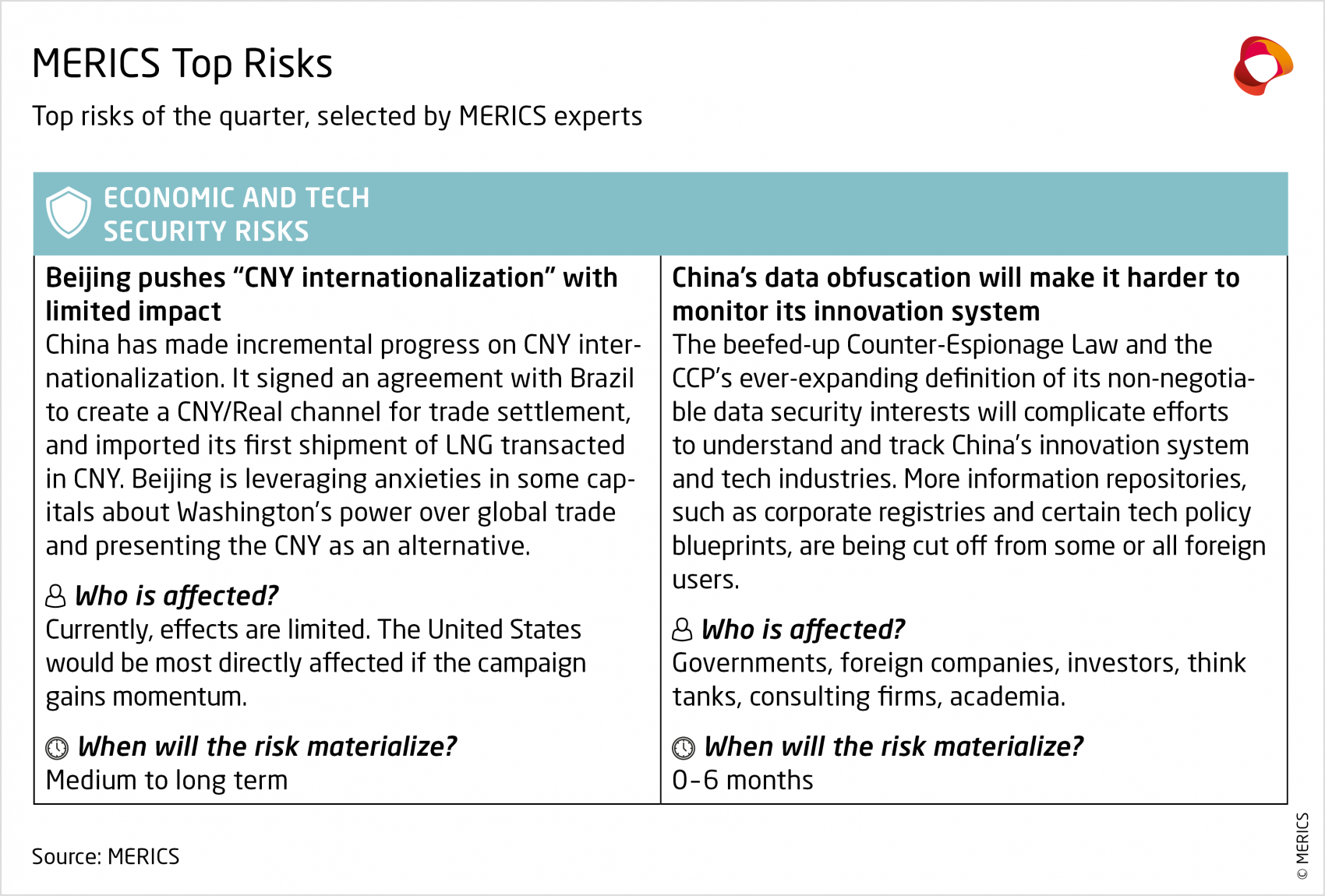

Growing scrutiny of outbound information flows disrupts business

Although Beijing has promoted a narrative of a “great reopening” since dropping its zero-Covid policy, new measures and policy developments are eroding the sustainability of some companies in China. They will also seriously undermine the quantity and credibility of economic information coming out of China.

Policymakers have amended the Counter-Espionage Law and cracked down on information channels. Apparently, they were concerned about foreign actors gathering information to tie Chinese companies to sensitive projects – like Beijing’s civil-military fusion strategy – that might expose Chinese firms to US export restrictions and other sanctions. The amendment greatly expands the scope of the law from “state secrets” to anything related to “national security”, which itself has considerable scope under Xi.

The amendments present massive compliance risks for Chinese and foreign companies alike, and make it much more challenging to conduct a risk assessment from overseas. Blocking access to Chinese databases, archives, etc. will (to the degree that they are restricted) degrade the precision of corporate or government analysis of risks and opportunities in China.

There could be multiple, varied impacts. Due diligence consultancies may be unable to reliably assess a company’s exposure to forced labor; banks and insurers may have to take a more conservative stance on rates related to investment and insurance for assets in China; policymakers may have a more partial picture of what is happening in China, thereby raising the risk of miscalculation and escalation.

China plays the long game in the tech war with the United States

Beijing initially responded timidly when the Biden administration published its package of export control measures targeting China’s chip and Artificial Intelligence industries last October. It filed a lawsuit at the WTO and issued verbal threats, including to the Netherlands and Japan (both of which have since announced export restrictions on advanced chipmaking tools). But Beijing was mostly scrambling to assess the damage and figure out ways to support its industry.

Now, however, the elements of China’s strategy to defend its interests and retaliate against tech trade restrictions by the United States, its allies and partners, have become clearer. Beijing is playing the long game here, carefully testing the arsenal of regulatory and legal tools it has patiently built up over a decade. Authorities are dragging their feet on several tech sector mergers. Meanwhile, US-based memory chipmaker Micron failed a cybersecurity review. Authorities determined its products pose security risks to China’s critical information infrastructure supply chain. Foreign companies should take note of Beijing's definition of supply chain security: it also considers the risk of disruptions due to political, diplomatic, and trade factors.

In addition to deploying its toolkit of retaliatory and coercive instruments, China continues to fine-tune its export controls regime to protect its economic, industrial and tech security interests—and to be able to weaponize the chokepoints it controls if push comes to shove. Foreign policymakers and industry are anxiously awaiting the outcome of proposed revisions to a key Chinese tech export catalogue which, if enacted, could have wide ramifications for industries ranging from green technologies to microelectronics.

Looking forward

What to watch in the months ahead

- June 2-4: The Shangri-La Dialogue organized by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) will take place in Singapore, with reported participation by China’s Minister of Defense, Li Shangfu, and US Secretary of Defense, Lloyd Austin. The first in-person meeting between the two may take place on the sidelines of the event.

- June 20: This year’s Sino-German government consultations in Berlin are expected to tackle points of friction, such as Taiwan and the opening of China’s market to German firms, along with opportunities of collaboration on topics like climate change. The publication of Germany’s long-awaited China Strategy is expected in the weeks following the talks.

- June-December: Italy will decide whether to renew its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) memorandum of understanding with China; reports suggest Rome will opt to cancel it. The original MoU was signed in March 2019 and is set to auto-renew in March 2024 unless one of the parties gives notice by December 2023.

- Endnotes

-

1 | https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202303/t20230311_11039241.html

2 | https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/18/china-ready-to-broker-israel-palestine-peace-talks-says-foreign-minister; https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202304/t20230426_11066785.html

3 | https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/2461_663310/202302/t20230216_11025999.html

4 | These include China’s mediation in Afghanistan, in the Iran-Saudi Arabia and Myanmar-Bangladesh conflicts, its participation in Iran nuclear deal talks, and offers to mediate of facilitate talks between Ukraine and Russia, Israel and Palestine, in Yemen and in the Horn of Africa.

5 | https://thediplomat.com/2023/03/the-broader-context-behind-chinas-mediation-between-iran-and-saudi-arabia/

6 | https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/01/despite-high-stakes-ethiopia-china-sits-sidelines-peace-efforts

7 | https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202302/t20230224_11030713.html

8 | https://merics.org/en/comment/china-conflict-mediator

9 | https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202302/t20230221_11028348.html

10 | https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-economy/article/3210624/chinas-top-diplomat-backs-hong-kong-international-mediation-centre-city-launches-preparatory-office