Updating the EU action plan on China: De-risk, engage, coordinate

At a glance

- The EU’s China policy needs recalibration: Since the unveiling of the EU-China Strategic Outlook in 2019, the EU has made significant progress in developing a range of defensive policies. Yet the bloc now needs to update the Strategic Outlook’s action points to reflect changes in China and on the global stage.

- Update, not redraw: The new action plan can continue to be guided by the three-pronged approach (cooperation partner, economic competitor, systemic rival), but should account for the growing weight of the latter two components in EU-China relations.

- We propose three baskets of policy action:

- De-risk: mitigate the EU’s strategic dependence on and vulnerabilities to China

- Engage: establish a baseline for cooperation with China in areas of common interest

- Coordinate: increase synergy on China-related knowledge within the EU and among partners

- Build up own capacity to act: An updated action plan on China would expand autonomous measures to ensure that European strategic interests can be secured, even when China or other partners do not embrace the EU’s proposals for multilateral solutions.

- Seek cooperation but prepare for lack thereof: An updated plan should continue to seek cooperative measures with China while being aware of Beijing’s readiness to use talks as means for strategic stalling.

- Create structures to boost European unity towards China: It is needed more than ever. Systematizing alignment processes among European institutions, member states and relevant stakeholders can help to improve internal alignment.

Updating the EU’s China policy: Key lessons from implementing the 2019 Strategic Outlook

- Improve internal coordination on China: The EU’s approach to China – as partner, competitor and systemic rival – in the 2019 Strategic Outlook brought cohesion to its position. But member states and EU institutions diverged in their implementation of some of the Strategic Outlook’s 10 action points. New structures should help define priorities and goals and coordinate member states’ communication with China.

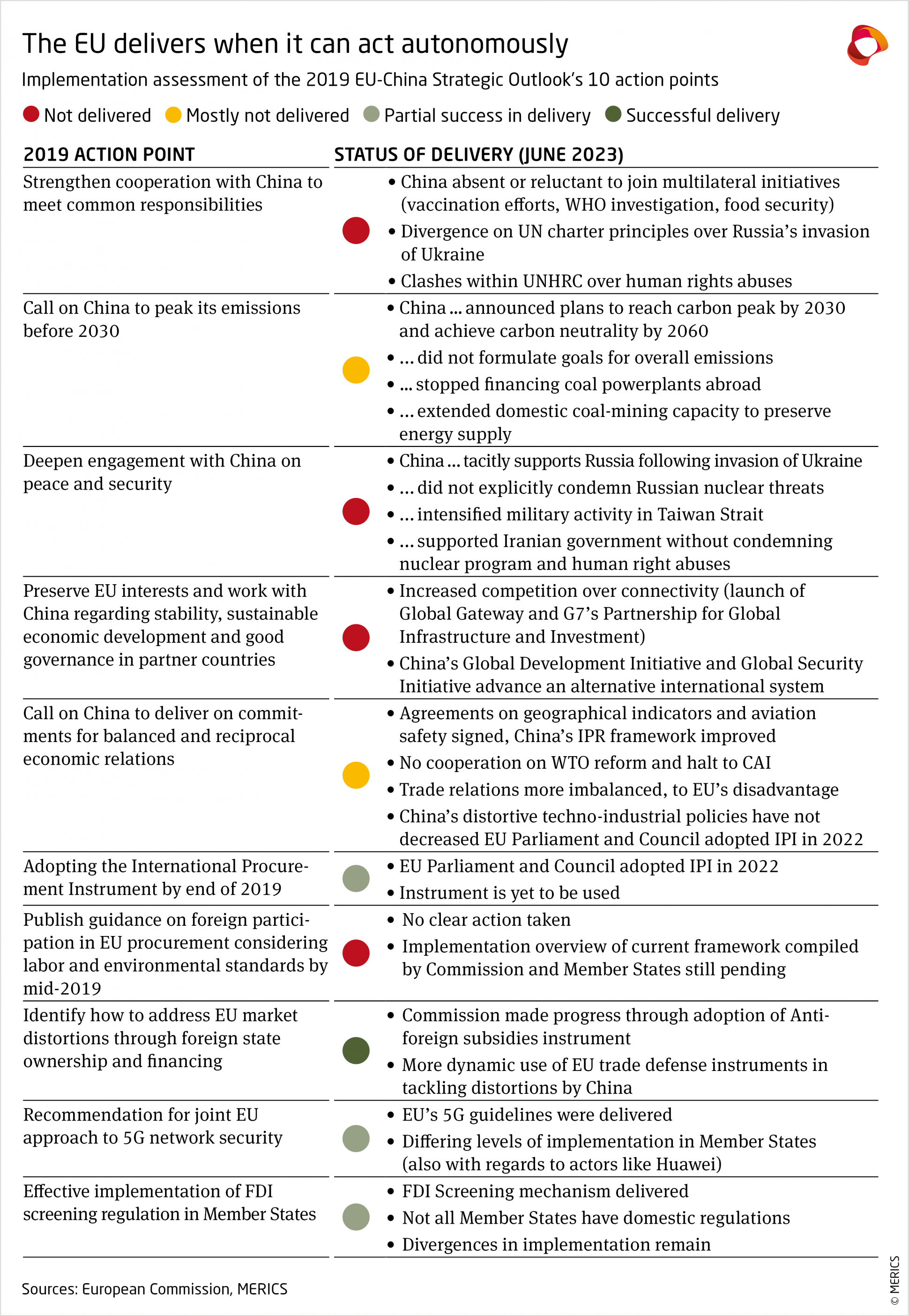

- Strengthen autonomous measures and boost resilience: The EU has been most successful with implementing its action plan when acting autonomously, especially developing new policy tools. The updated plan should therefore complement collaborative initiatives with options for independent actions should collaboration not bear fruit. This will boost the EU’s international bargaining power. To bolster resilience, the EU should also close technical and political loopholes that limit the efficiency of its policy tools.

- Expand coalitions to steer China towards rules-based multilateralism: Beijing has shown limited support for rules-based multilateral solutions to global challenges or for constructive reforms to the international system. Instead, it has been building its influence within multilateral bodies on issues that directly impact its interests and prioritizing unilateral and bilateral measures (e.g., on pandemic response or climate crisis). Furthermore, it promoted an alternative, state-led “true multilateralism” that it defines through its Global Development, Security, Civilization and Data Security Initiatives. The lack of substantive contribution to discussions on reform of multilateral institutions might even indicate Beijing engages some of those conversations with the objective of strategic stalling.

- Coordinate common concerns and vigorously invest in engaging the Global South, beyond traditional, like-minded partners. The multilateral system needs reform that accommodates both the EU’s principles and interests as well as developing countries’ concerns – to effectively compete with alternative offers and have a chance of overcoming inertia.

De-risk, engage, coordinate: Updating the EU’s China policy

Significant developments in China and on the global stage in recent years call for an update to the action plan included within the EU’s 2019 Strategic Outlook on China. This key policy document established a common approach to relations with China – engaging it as a partner for cooperation and negotiation, economic competitor and systemic rival. While the overall flexible approach of the Outlook remains useful, the action points themselves require an update to respond to the new political reality and to factor in the lessons learned from how member states implemented the Strategic Outlook’s 10 action points.

Since 2019, China has become more centralized, securitized, and assertive. The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) signaled further party-led centralization, securitization that expands into the economy, as well as increased use of laws as a weapon against rivals (e.g., China’s new anti-espionage law or Hong Kong’s National Security Law). The party state has asserted its market-interventionist and assertive foreign policy course that runs counter to the spirit of the rules-based international order, as well as to European hopes that economic ties would bring the PRC closer to its own set of norms and preferences.

Beijing has become more confrontational in the Taiwan Strait and more ambitious in controlling international discourse and promoting visions of an alternative international order (e.g., through Global Development, Security, Civilization and Data Security Initiatives). Meanwhile, the geopolitical situation has become more volatile due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the intensifying Sino-American competition that is fueling bifurcation of the international order. Beijing’s unwillingness to confront Moscow over its invasion of Ukraine in particular tests its credibility as a viable partner for the EU.

The EU already began to respond to these changes in its October 2022 European External Action Service (EEAS) paper on China, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s de-risking proposal in March 2023 and China discussions during the May 2023 Gymnich meeting of the EU Foreign Affairs Council. The EU-China summit and the European Council discussions in June 2023 will be key to developing a more coordinated position on China. The task is even more urgent as the recent flurry of diplomatic exchanges between China and the member states necessitates creating a more coordinated EU position on China policy. The upcoming European Parliament elections and the new term of the European Commission in 2024 also merit the need over the coming months to agree on a tactical action plan on China to prevent disruptions to EU China policy in the course of electoral transitions.

Paying heed to the increasing importance of competition and rivalry

The new EU action plan should focus on defining the tactical level of the EU’s China policy and recognize the increased importance of systemic rivalry and economic competition, even as the EU maintains its approach to China as partner, competitor and rival. A new set of action points will help the EU execute its China policy around three objectives:

- De-risk China relations – Mitigate strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities that China could exploit

- Engage China and partners – Establish a baseline for constructive engagement with Beijing and strengthen the rules-based international order through working with a variety of partners

- Coordinate internal resources and cooperation with partners on China – Create structures for improved policy planning, knowledge exchange and increase China literacy among stakeholders

Key ways to DE-RISK

1. Create an EU risk assessment framework with corresponding response measures

De-risking is the guiding concept proposed by the European Commission to manage and reduce the EU’s economic dependencies and vulnerabilities – such as recent supply-chain tensions or reliance on imports of critical raw materials from specific locations. It offers a broad conceptual basis for multiple policies and approaches, including the risk assessments of partners now proposed in the EU’s economic security strategy. Although de-risking the economic relationship is the main focus of this section, de-risking is about more than just economic interactions. De-risking is also about reducing the risks to European values and to democracy.

Aligning methodologies that are also applied consistently by member states, the EU can assess the risks posed by China (and other countries) without discriminating against China but letting the results of the assessment indicate that certain aspects of the relationship with China pose high risks for the EU. The risk criteria would be as objective as possible but must be informed by experience. The risk assessment would underline Beijing’s track record of economic coercion and non-market practices as well as the EU impact of its goal of technological self-sufficiency, all elements that increase the risk of disruption. To ensure success, European firms in strategic sectors (already identified by the European Commission in reports published in 2021 and 2022) would disclose their degree of exposure to the Chinese market in terms of investment, revenue, profits and value-chains where public information is insufficient. The EU’s early warning system (currently under development) could then be finetuned based on this information.

The risk assessment will enable the EU, member states and the business community to first collect comparable data on existing risks, their impact, and ability to manage them. Second, it would allow for the adoption of a much-needed common language for the identification of such risks and how to manage them, and thus align different policies and their implementation that match shared objectives of de-risking. During that process, the characteristics of different goods should be considered in shaping the best risk-management approach (i.e., for smaller goods stockpiling may be the answer). The assessment outcomes will help prioritize and coordinate measures (also for member states) such as diversifying, stockpiling, recycling, connecting local industries in strategic sectors or developing domestic capacities, as well as helping to identify potential gaps in the existing toolbox. The results of the risk assessment should be considered during the development and coordination of strategies – like in the implementation of the Commission’s Global Gateway program, trade agreements or other bilateral agreements.

2. Build and strengthen global networks to reduce dependency on China

Building new economic ties and strengthening existing ones will help reduce strategic dependencies on China. Beijing has long understood that engagement with developing economies is key to the future of its economic prosperity and power. Besides strengthening relationships with traditional partners such as the G7, the EU should focus on its relationship with developing economies. Free Trade Agreements (FTA), the new format of the Trade and Technology Council (TTC), Global Gateway and other bilateral arrangements can help the EU diversify and solidify its own supply chain as well as global supply chains. This helps to avoid indirect dependencies on China via third countries and promote standards that are respectful of human, labor and environmental rights – rights that are at the core of the EU’s value system.

Although bilateral engagements are the fastest and most efficient way to manage vulnerabilities, they risk overlooking indirect dependencies. The Commission has already adopted a principle not to depend heavily on one source. Strengthening plurilateral engagement would further contribute to safeguarding effective diversification while maintaining a degree of openness.

3. Create EU guidelines on informed subnational and non-state engagement

Chinese actors’ direct engagement with city or local-level European authorities and institutions such as universities and research centers has been unfolding with minimal or limited scrutiny and often with little awareness from European sub-national actors over the underlying risks in this engagement, limiting the EU’s supranational strategic awareness. When the EU drafted its Strategic Outlook in 2019, there was little conversation about China’s interference in civil society. Since then, the EU has increased its awareness and ability to respond, although more work is required. For example, efforts of the EEAS in tracking Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) originating from China are still to be explicitly mandated by the Council, which could unlock additional resources and improve involvement of member states in responding to China-related FIMI cases.

National security is a competence of each member state. However, foreign interference in one member state has repercussions for others. For this reason, the EU should draft guidelines and recommendations (e.g., actionable checklists) as policy blueprints that member states could divulge to local authorities, institutions and civil society engaging with partners from high-risk countries. The approach would be rooted in the idea of boosting democratic resilience through a whole-of-society approach with the EU guidelines acting as suggestions for member states to sensitize local actors to FIMI related challenges and empower them to respond autonomously. The level of risk associated with each partner would be identified via the proposed risk assessment, defined through criteria that can be applied to any actor. This should include guidelines on knowledge security, information security related to media partnerships and publishing/broadcasting of information, and expansion of the 2022 toolkit on mitigating foreign interference in research and innovation.

Key ways to ENGAGE

1. Boost strategic communication and response preparedness on strategic issues

The consistency of messaging between member states is key prerequisite for an effective EU diplomatic strategic deterrence towards China. Agreeing on a set of common messages on key issues of interest – like China’s positioning towards Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or the tensions in the Taiwan Strait – will help the EU reduce its vulnerability in strategic communication and boost diplomatic deterrence ability. In that context, the EU should also consider bolstering its capacity for common response and communication in some extreme scenarios to ensure its preparedness, should they materialize. For instance, it should agree a set of common messages to be deployed by EU capitals and discuss a set of common measures aimed at supporting the status quo in the Taiwan Strait and at preventing China from providing more substantial support for Russia in its aggression against Ukraine.

To facilitate collective communication practices, the EEAS and COASI (Asia-Oceania Working Party of the Council of the EU) could conduct messaging alignment discussions – including for public-facing readouts and statements – ahead of major interactions with Chinese officials when EU’s strategic interests are being discussed. In a similar vein, common practices in terms of timely publications of robust readouts after meetings with Chinese counterparts should be established to prevent Chinese narratives from dominating the discourse space in the absence of European positions.

2. Strengthen the rules-based international order through reform coalitions – with or without China

Collective solutions to strengthen the rules-based international order can address areas where the emergence of China has shaken the existing framework and threatens the rule of law in favor of power dictating law. Such actions weaken smaller actors, the international competition rulebook (the WTO) and international debt restructuring. The goal should be for China to constructively participate in reforms that strengthen rules-based multilateralism.

However, based on Beijing’s limited enthusiasm for such initiatives in the past, the EU should be ready to build coalitions for reforms, especially with developing countries, that could incentivize China to join. This could take the form of plurilateral agreements among countries willing to support the norms of a rules-based system with or without China. Getting China on board should not come at the cost of the core principles of transparency, fairness and predictability. Proposed or established plurilateral upgrades will incentivize China to genuinely take part in negotiations focused on multilateral solutions.

When engaging China on those matters, Europeans need to be clear, especially internally, of their objectives in those exchanges. This would help to monitor the efficiency of dialogues with China over time, manage expectations and foster consistency with broader European endeavors. The risk of Beijing only engaging the EU to pursue strategic stalling and extend the beneficial status quo, ought to be considered. External communication to partners and civil society should more clearly underline that a functional rule-based international order foremost benefits the players with the least bargaining power, often developing countries. This communication dimension shall, however, not prevent European actors from better integrating the views and interests of less developed actors.

3. Develop ground rules for constructive green cooperation/competition with China

The EU and China should find common ground for action on environmental challenges. This is a shared interest of both parties, and cooperation should not require European partners to meet unrelated conditions – e.g., it should not be affected by European exchanges with Taiwanese partners. Beyond bilateral efforts to strengthen international discussions and frameworks on the environment, the EU should invest in establishing green standards with China, including for goods, the environmental impact of their production, and for the design of public investment in relevant sectors.

As a condition for access to the single market, the EU is setting high-level green standards for products with a high environmental impact. The next step is a common certification and assessment system to maximize the effect of these measures on its environmental goals. Products made of wood, batteries and even extractive minerals, as well as those covered by the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are obvious priorities, as is international transport. Efforts for international cooperation should not be conditioned by China’s participation. Still, China’s economic and political significance in the green transition make it a priority partner, so it is prudent for the EU to consider China’s concerns in its proposals for a certification system. Areas of cooperation ought to be defined with the competitive implications in mind, considering the perspective of European firms.

Similarly, to ensure its measures are internationally accepted, the EU should invest resources in explaining and presenting better the European green standards, their certification procedures, the funding provided to facilitate reaching those standards and their respect and alignment with international regulations.

Key ways to COORDINATE

1. Create an EU China Action Plan review and update mechanism

Improving internal coordination, both between stakeholders and policies, is a priority for the EU’s China policy. Conducting periodic assessments of the implementation of the action points and updating them in two-year cycles can help to ensure that China-related policy measures are more coherently implemented by the member states, to avoid miscommunication and align EU member states more closely on a tactical-level agenda of EU China policy. It would serve as the next step towards a more united China policy standing upon the common foundation of the Strategic Outlook’s three-pronged approach.

The assessment should be carried out by the EEAS in coordination with COASI and include an outreach exercise to a wider group of relevant stakeholders (such as MEPs, business representatives, NGOs, research institutions, etc) and input from EU and member state delegations in Beijing. The conclusions of the assessments and a proposal of an update of the action points could then be discussed on the COREPER level and, if deemed appropriate, put on the agenda of the Foreign Affairs Council or the European Council.

With a growing number of actors and policy instruments being involved or impacted by the China policy, such a review process could narrow the gap between strategic thinking and the practical, operational-level actions of the EU and its member states on China policy. Furthermore, the biannual rhythm could also help to structure the China agenda of subsequent European Commissions, helping to ensure effective delivery of policy projects between the EU terms.

The revision exercise would also help to limit information asymmetry between the various EU actors and China (which coordinates exchanges between its own officials and member states). Reducing this asymmetry, which currently benefits Beijing, would hinder divide and rule tactics.

2. Develop the EU’s understanding of China policies of partners

China’s policies and initiatives are increasingly geared towards using Beijing’s engagement with third countries to reshape the international order. Better understanding its partners’ positions on China will help the EU respond to the systemic challenge that Beijing’s efforts present. Exchanges with partner countries already take place for example through the dedicated EU-US High-level Dialogue on China and the coordination efforts within the G7 framework. The EU should expand such efforts and map where its interests overlap with the governments and societies of partner countries and in alignment with them raise concerns and hopes for Beijing’s policies. Such efforts should include developing countries to build non-Eurocentric perspectives into coalitions. This also helps refute labels like “West vs. Rest” or “Global North vs. Global South” that constrain EU policies or validate Beijing’s narratives.

For instance, regular information gathering by contact points on China in EU delegations could lead to quarterly updates for the EEAS on China’s activity and evolving footprint in the host countries and their China related policies. This could help map China-related opportunities or concerns of third countries and bolster the EU’s capacity to engage in the battle of narratives and the battle of offers. The outreach should also include discussions with European businesses in said third countries to identify the challenges they face from, oftentimes subsidized, Chinese competitors.

Such an effort would make engaging with new partners on China issues easier and could be used to inform the EU’s outward facing activities within the scope of, for instance, the Global Gateway or Neighborhood Policies. EEAS could share the results with member states in the framework of existing exchanges, as they often lack the resources to conduct such consistent mapping on their own. To facilitate that, the member states should allocate additional resources to process data on Chinese activity in third countries on the EU level.

3. Develop and pool China expertise including for training measures

China is a new and complex global power whose decisions have an impact on a growing range of the EU’s cross-sectoral policy debates – from industrial policy to knowledge security. Yet, EU and national agencies often do not have the capacity and/or the in-house expertise to focus on China and the level of knowledge on China remains unevenly distributed and prioritized within governmental agencies across the EU. The EU has been building its knowledge on China through EU-sponsored initiatives such as China-related projects under the Horizon Europe or the China in Europe Research Network (CHERN), which can provide governmental actors with a pool of expertise to tap into. But connecting the ever-growing pool of government institutions impacted by China to this pool of expertise remains a challenge.

To overcome this, the EU and member states should consider investing in long-term efforts to strengthen applied European China research, either in ways similar to Bruegel or the new institute of geopolitics in Brussels or in a more networked fashion. They should begin by establishing dedicated annual China trainings for European officials to help them contextualize Beijing’s actions within their field of work. These should be offered not only to officials who directly and officially deal with China, but especially to those who cover issue areas strongly related to China. Some of the EU’s like-minded partners have already taken such measures.

This MERICS Report is part of the project “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.