From opportunity to risk: The changing economic security policies vis-à-vis China

Amid global economic uncertainty and tensions, many countries have been adopting ever larger and more complex sets of policies to make sure their economies can resist shocks and pressure by third countries. Francesca Ghiretti says the changing global economic policy environment can also be explained as a response to China. At the same time, Beijing is quickly expanding its own economic security policies. Her analysis is accompanied by a slidedeck that provides context for and deeper insights on the topic.

Fear and nationalism are increasingly driving the global economic agenda. Recent global upheavals – from pandemic supply chain issues to war in Europe, rising nationalism and authoritarian governments – have put both security and resilience at the center of economic security policy worldwide. Where advanced economies like the US, Europe, and Japan once viewed China’s competitiveness as an economic opportunity, they now see it as a security risk.

China’s heavy subsidization of its enterprises, sweeping industrial policy, strategic use of foreign policy to advance economic goals and weaponization of economic linkages to pressure third countries are driving the expansion of economic security measures. Such policies include investment screening (to examine and eventually block investments that pose a security threat) and enhanced export controls (to control the export of products and services with dual civilian and military use).

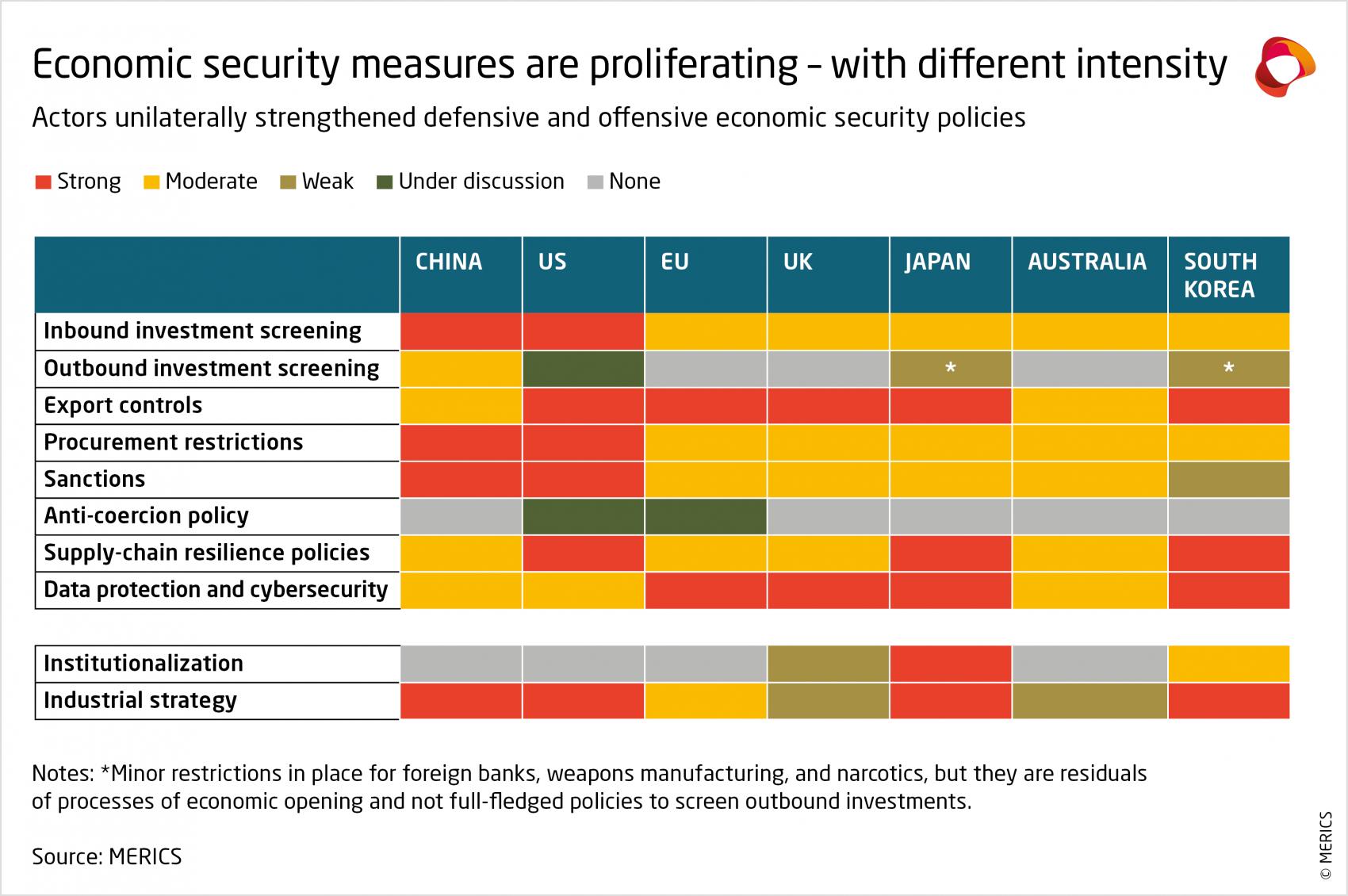

Countries are adopting ever larger and more complex sets of policies to protect their security and strategic assets, and to diversify their supply chains– all to make sure they are not exposed to security risks and that their economies are resistant to shocks and weaponization by third countries. Countries have unilaterally introduced a wide variety of tools with very different functions and effects. Just five years ago, there were much fewer and weaker unilaterally adopted economic security measures.

Three tensions underpin the evolution of economic security policymaking

Unilateral economic security policies are on the rise everywhere and their scope is expanding, offering little salve for the already creaky multilateral system and its international institutions. The future of the rules-based global system looks to be one of disparate policies that prioritize a broadening interpretation of national security and resilience over global economic gains, with ad-hoc collaboration and coordination in areas of common interest for select countries.

Three main tensions emerge from the current debates regarding economic security policies such as outbound investments screening, export controls, and supply chain resilience. The first is the need to balance the protection of national security and the will to uphold an open economy. The second pits unilateral against multilateral policymaking. The third regards the approach to China.

1. National security vs open economy

While national security is a common denominator of economic security policymaking, how actors interpret the term, and its scope differs greatly. Policymakers are increasingly buying into a concept of national security that includes “resilience”. The expansion of dual-use technology is one issue forcing countries to widen their concept of national security.

China, for example, is pursuing a policy of civil-military technology fusions that blurs the line between military and civilian technologies. China is also leveraging its economic power to influence other actors’ decisions and behavior. That, in turn, has driven others to consider resilience a national security priority, with the aim of making their own economies as resilient as possible against external shocks and influences, and to incorporate this into their economic security agenda. However, economic security is in a policy area that in most countries does not have an institutional “home”, with the exception of Japan’s Minister for Economic Security. The prioritization of economic security should be reflected in the institutional setting.

2. Unilateral vs multilateral

The logic of resilience and the need to be less dependent on the Chinese market has spurred a new wave of unilateral economic security and industrial polices. However, when focused solely on advantages for the domestic market – and without coordination with partners – they can be damaging. Recent prominent examples are the new US semiconductor export controls and Inflation Reduction Act, which have created problems for partners such as the EU. The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, incentivizes European companies to move operations to the US. The EU and US are trying to resolve these issues, but they show how uncoordinated policies can have broad unintended effects on partners. Currently, coordination may take place in exclusive formats such as the G7 or the Trade and Technology Council (TTC), but a truly multilateral framework for economic security would offer a platform not only for coordination of initiatives and responses, but also for the operationalization of a new concept of collective economic security.

3. China strategy

For all countries the issue of economic security is officially only indirectly connected to China – it regards China only if it acts in breach of their policies. The US however is creating economic security regulations that by reflecting their China strategy directly target China. The new US export controls on semiconductors, which targets the export of products, services, knowledge, and labor to China, is a prime example of an approach to economic security rooted in the desire to outcompete and contain China.

The difference in approaches can partially be explained by the differences in the actors’ official approach to China. In its most recent national security strategy, the US officially recognized China as a national security challenge. Other countries maintain an official position that does not view China as national security threat.

Debating outbound investment screening – an option for a new vision in economic security policy

Such fundamental discussions will be front and center in the economic security agenda in the months to come. This requires a structural re-think of the rules of globalization. Screening of outbound direct investments offers fertile grounds to debate these tensions.

Mainly in response to China’s perceived predatory investments, most advanced economies now screen inbound investments, although with major differences in regimes. But no one officially screens outbound investments, such as European firms investing in China. Inbound investment screening mechanisms have been growing in number and scope since the mid-2010s and are now increasingly the norm, but it took years and a lot of effort.

Outbound investments screening, however, faces additional obstacles. Japan and South Korea already have minor restrictions in place. These are residuals of an economic system in place before they began to open their economies. As such, they cover limited areas – foreign banks, weapons manufacturing, and narcotics.

US legislators, on the other hand, have been proposing new limitations targeting previously non-restricted outflow of capital and countries like China, Iran, and North Korea. And the European Commission will consider the policy in 2023, the same year in which it will review the inbound FDI screening regulation. In other words, although the result may appear similar, the “screening systems” in Japan and South Korea and that proposed by the US and debated by the EU are the result of two opposite processes and drives.

It should be noted that Japan and South Korea’s economic opening has been affected by new considerations about economic security, and they, too, are now weighing a possible outbound investment screening and have been areas adopting new economic security policies. In 2020, South Korea revised the Act on Prevention of Divulgence and Protection of Industrial Technology, which regulates not only foreign mergers and acquisitions in national core technologies, but also the export of core technologies that received government support during R&D. And Japan has adopted the Economic Security Promotion Act to secure supply chains for its economy and safeguard home-grown innovation.

The National Critical Capabilities Defense Act (NCCDA) proposed by US legislators aims to protect US technological knowledge and prevent the support of Chinese technologies with US money and know-how. With its most recent export controls, the US has made clear that it does not shy away from regulations specifically targeting China, and since it has already requested that partners use their own export controls to do the same, it is likely to ask the same from a policy screening outbound investments. But, at least for now, the EU will continue to opt for policies that do not target a specific country (country-agnostic), including any future mechanism to screen outbound investments.

Outbound investment screenings should focus on sensitive technologies and strategic sectors

Without a specific geographical target, the EU’s investments screening effort will be more labor- and capital-intensive, as in theory any destination country can be screened. The EU should thus first narrow down the focus to direct investments only and target specific sectors and/or items.

A report by the Rhodium Group has shown that large European outbound investments into China are clustered in certain sectors such as automotive, food processing and distribution, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, and chemicals. Most importantly, they are made by a handful of companies.1

Ideally, the main target should focus both on quality and quantity of the investments. The analysis should not only include large investments, but also small investments in sensitive technologies and strategic sectors, for which a more granular screening is required. In line with the suggestions made by a report from the Atlantic Council for a phased approach to the US screening mechanism for outbound investments, albeit with different objectives and scope, a round of notifications of outbound investments can help the EU obtain a better picture of what is happening. Subsequently, the EU can make an informed decision if such new instrument is needed and how it should look like. Despite the differences in targets, coordination with the US and other partners is recommended to avoid undesired repercussions from the unilateral adoption of uncoordinated policies to screen outbound investments.

Outbound investments screening and resilience

Some European outbound investments may pose risks to EU security. However, national security should not be the sole concern, resilience should also be considered. For example, EU automotive sector investments in China may not be a direct security threat but at a time when the EU is trying to better manage overdependencies, those investments can increase the EU’s dependency on China, which has been known to use economic coercion. While that is not the case for all sectors and it may not be an immediate security risk, overdependencies constrain the EU’s room to maneuver.

In that regard, the debate on outbound investments can help shape an EU economic security framework that offers greater prominence to resilience and allows it to make choices minimizing constraints in case of disruptions. This approach would be based on longer-term questions of “Open Strategic Autonomy” rather than immediate security considerations and it should form the basis of all EU economic security policymaking.

Nonetheless, it is important to understand that an important part of the overdependency of European companies from China will not be mitigated by screening outbound investments, which only covers a very limited part of the companies’ exposure in China.

China’s economic security is also quickly expanding

Much, although not all, of the new restrictions adopted by the US, the EU, the UK, Australia, Japan and South Korea are in response to China’s expansion of its global presence, its perceived unfair economic competitiveness, and its use of economic coercion at different degrees. External perceptions aside, however, it is evident that in China, too, security increasingly trumps openness.

As reiterated during the 20th Party Congress and then in Davos, China still officially promotes opening up and global trade. But many of its policies prepare for a worst-case scenario in which China’s reliance on external actors may be used against it. These the incoming foreign relations law.

Economic security is a cornerstone of China’s all-encompassing concept of national security and national security is viewed as fundamental for China’s economic development. China’s new measures and updates to safeguard economic security are closely linked to its relationship with developments outside of China, especially in the US. However, they are also the result of China’s effort to strengthen its regulatory framework. For example, China adopted its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law in 2021 to protect itself against potential primary and secondary sanctions by the US, but also to provide a legal justification to already existing practices.

If China continues to develop policies also by weighing the actions of the US, then China is likely to fine tune its own instrument for screening outbound investments should the US adopt an outbound investments screening.

Party and State Leader Xi Jinping has labelled outbound investments a matter of national security. As Beijing tries to boost innovation at home and produce technologies domestically, and the US explicitly targets Chinese innovation with its policies, broader application can be expected.

China introduced a form of screening mechanism for outbound investments in 2018 – the Administrative Measures for Enterprise Outbound Investments (AMEOI). It is currently limited to countries that do not have diplomatic ties with China, which experience domestic unrest or are hit by sanctions that China complies with. Transactions below USD 300 million are exempted but it also applies to foreign subsidies of Chinese companies.

The measures also apply to sensitive industries (including military, communications, media, real estate, energy and illicit industries such as pornography). The wording of the regulation leaves room for its future expansion, such as its application to other sectors and countries.

The global economic security landscape is becoming more complex and filled with new and evolving economic security measures to protect national security and resilience. The changing environment comes in response to China, while China itself adopts policies to protect itself from foreign countries. Three main tensions have emerged and are shaping economic security agendas globally: balancing security and economy; defending and boosting home economic security while avoiding unintended external effects; and the approach to China. In such a situation, the debate on whether to adopt outbound investments screening is one that can bring clarity to some of the tensions that underlie economic security policymaking today.

- Endnotes

-

1 | The study by the Rhodium Group only analyzes investments above 1 million euros. To adopt an effectively sector-targeted regulation an analysis of investments below 1 million should also be carried out.