China-Russia + Research cooperation + EU-Africa Summit

ANALYSIS

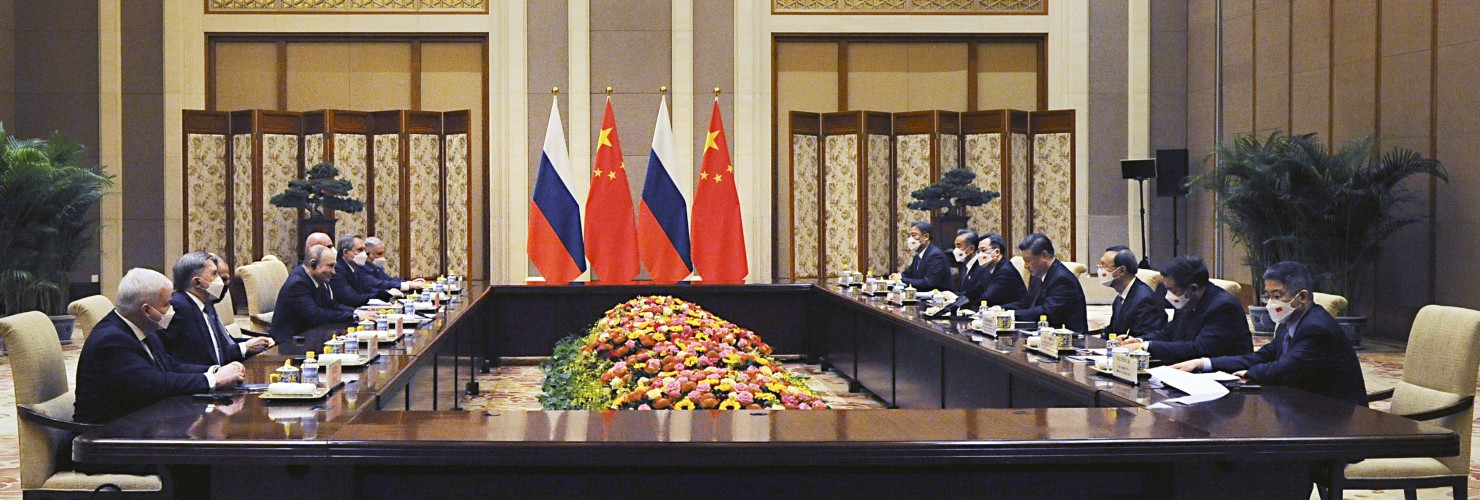

What does enhanced China-Russia coordination mean for the EU?

by Grzegorz Stec

The China-Russia joint statement opens a new chapter in Beijing-Moscow cooperation, creating a relationship that the two partners describe as “superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era” with “no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation”. It was accompanied by a range of other agreements such as a 30-year gas deal or cooperation between satellite navigation systems GLONASS and Beidou.

Beijing has for the first time explicitly expressed support for Moscow’s stance about its security in Eastern Europe and opposition to further NATO enlargement in the region. The two countries have also jointly opposed the security pact between Australia, the UK and the United States (AUKUS) and the “formation of closed bloc structures and opposing camps” in the Indo-Pacific.

The joint statement includes a mutual promotion of global tech standards, increasing military coordination and expanding economic crossovers between the Belt and Road Initiative and Eurasian Economic Union. The pair also emphasized their ideological kinship through commitment to “democratization of international relations” and opposition to “color revolutions”, regarded as foreign interference by liberal democracies.

Not allied, but strategically coordinated

A strategic coordination rather than a formal alliance is rooted in a shared assessment of the two countries’ aligned strategic interests. Such shared assessments might originate from a similar political psychology of their elites, focused on hard power and regime stability, while aligned interests include supporting authoritarian political models or striving for multipolarity. Either way, both have a vital interest in redefining the Western-led rules-based international order. While the edge of this coordination is aimed primarily at the United States, the EU is also seen as a challenge given its commitment to democratic values and a market-driven approach.

Notably, the statement included more Chinese foreign policy concepts such as the “community of common destiny for mankind” or Beijing’s rhetoric on “democratization” than previous similar statements, revealing how the power balance in Sino-Russian relations continuously shifts in Beijing’s favor.

While Beijing’s economic and technological power paired with global influence is increasing, Moscow is struggling to forestall the retrenchment of its position. Consequently, there are a range of issues: a level of mutual mistrust as Moscow strives to retain achievable levels of autonomy — limiting Chinese investments in the country, occasional divergences — in the Arctic and prospectively in Central Asia, or limitations to political commitment — lack of recognition of the annexation of Crimea by China, and Russia’s reluctance to support China’s South China Sea claims.

However, these tensions do not meritshould not prompt European attempts to derail the Sino-Russian relationship. For Moscow, increasing dependence on China is undesirable but also unavoidable given the lack of better strategic alternatives. Any concessions offered by the European side in the near future would therefore only be leveraged tactically without changing Moscow’s overall strategic calculations.

Implications for the EU

- The gradual loss of its strategic autonomy vis-à-vis Beijing could incentivize Moscow to diversify away from China in the long-term. However, current European initiatives to re-engage Russia are unlikely to bear fruit given the alignment of core interests between Russia and China.

- The EU should be aware of the impact of Sino-Russian coordination on the two states’ activities in Eastern Europe and in the Indo-Pacific (e.g., feeling secure on its eastern border, Russia moved many of its stationed troops to the Ukrainian border).

- The new gas contract and prospects for Beijing’s economic support decreases Russia’s fear of potential EU’s sanctions. China’s recent Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law is also an indication of determination to push back on such actions by the West.

- Systemic rivalry remains high on Moscow and Beijing’s agenda, with the first section of the joint statement devoted to “democracy”. The values-related tensions between Brussels and the two authoritarian capitals are likely to further escalate.;

- Beijing and Moscow may coordinate their pushback against the EU’s defensive mechanisms (e.g., opposition to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is mentioned in the statement) and may also attempt to undermine the EU’s coordination with like-minded partners on global standards and economic norms (e.g., under the Trade and Technology Council).

- Beijing and Moscow expressed commitment to readjusting the world order via the United Nations, BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organization and trilateral China-Russia-India format as platforms for facilitating that change. The EU needs to ensure that its proposals resonate not only with like-minded partners, but also with a wider body of developing countries.

Read more:

- Office of the President of Russia: Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development

- MERICS: From marriage of convenience to strategic partnership: China-Russia relations and the fight for global influence

- OSW: The Beijing-Moscow axis: The foundations of an asymmetric alliance

- PISM: How China and Russia Could Join Forces Against The European Union

China sponsored human rights research in Europe

by Vincent Brussee

Revelations from the Netherlands have put the spotlight on academic cooperation between China and Europe. The Dutch public broadcaster NOS uncovered that between 2018 and 2021, the Free University of Amsterdam received between EUR 250,000 and 300,000 annually from China’s Southwest University of Political Science & Law (SUPSL). The money went to fund the Free University’s Cross-Cultural Human Rights Centre (CCHRC) to “develop a global vision on human rights”.

This cooperation has raised more than a few eyebrows. Although the contract acknowledged adherence to academic independence, it did require the Centre to pay particular attention to alternative views of human rights that “do not get the attention they deserve because of existing power relations”. As the SUPSL was the sole funder of the Centre, it created a relationship of dependency. Indeed, the CCHRC’s website hosted articles lauding China’s human rights records, including one, since taken down, which asserted that “there is no discrimination of Uyghurs or other minorities in [Xinjiang]”.

Under heavy public pressure, the Free University suspended the CCHRC on January 26. Yet sources within the Centre made clear this was “definitely not the choice of the Centre”, with its director, Tom Zwart, making clear that he found nothing wrong with the cooperation. From this, it is reasonable to infer that the Centre was not so much subject to covert influence as it was largely aligned with Beijing’s outlook on human rights from the get-go.

Research cooperation with China remains difficult to assess and navigate

Although the human-rights nature of these revelations is unique, the question of how to navigate research cooperation with China is shared broadly. In a 2021 precedent, a contract between the University of Groningen (RUG) and its Confucius Institute revealed a RUG professor was forbidden from “damaging China’s image”. This month, reports from the United Kingdom showed British universities received around EUR 300 million from Chinese institutions. Cambridge University alone received around EUR 30 million from Huawei while its China Centre has been reported to train Chinese Communist Party officials through the Cambridge China Development Trust charity.

Three challenges have been highlighted in the responses to these revelations. First, there is a lack of national or even EU-level coordination. Second, many universities lack the combination of technical and China-specific expertise to assess potential risks, or this expertise remains compartmentalized. Third, even at the faculty level there is typically little idea of what research is financed by whom.

Policy responses are quickly coming in, but need to be balanced

Change is, however, on the way. The Dutch Ministry of Education has responded swiftly. It has launched a digital office that will advise on potentially sensitive scientific cooperation and will develop a nation-wide code of conduct. This came on top of the toolkit for preventing foreign interference in research, released by the European Commission earlier last month. These are steps in the right direction. However, the efficacy of these measures will hinge on the quality of the support offered. A fully functional system to prevent influence will require effective coordination between all actors and financial support.

Governments should, however, not throw the baby out with the bathwater. The development of a “witch hunt” is a real risk. In the United States, the Justice Department’s China Initiative has already led to xenophobic practices and racial profiling while only three out of 50 indictments involved actual suspicions of espionage. Rather, European initiatives should aim to incorporate Chinese voices to develop their response to Beijing’s influence. Indeed, many Chinese researchers have rich experiences managing the risks and complexities of Beijing’s interference. Only then can countries truly achieve their goals without harming the rights for which they stand.

Read more:

- University World News: University funding row raises Chinese influence fears

- Leiden Asia Centre: Towards Sustainable Europe-China Collaboration in Higher Education in Research

- The Times: British research ‘could help China build superweapons’

BUZZWORD OF THE WEEK

Systemic rivalry

The German Ministry of Foreign Affairs is reportedly preparing an interdepartmental document that advocates acknowledging “systemic rivalry” with Beijing. The document sparked media speculation about Berlin’s supposed plans to shift its China policy, particularly in the context of the new China strategy to be developed throughout this year.

However, highlighting the “systemic rivalry” – present already in the coalition agreement – may have more to do with the new administration’s ambition to bring its position on China closer to that of Brussels. Especially, seeing as the EU increasingly recognizes that its “three-pronged approach [to China] has shifted a bit to the third element, that of systemic rivalry.”

Read More:

REVIEW

A shiny new Chips Act for the EU

On February 8, the EU unveiled its program for strengthening resilience in the strategic supply chain of semiconductors and developing domestic capabilities in the sector. The topic has been high on the EU agenda. Throughout the pandemic the shortages of exports from Taiwan disrupted work of European companies including German car manufacturers, bringing many to a standstill.

What you need to know:

- What is the plan: The EU plans to produce 20 percent of the global supply of semiconductors by 2030. This is to be accomplished by investing a total of EUR 42 billion in public and private spending. The Commission pledged EUR 11 billion in EU public funds to be “directly provided” to improve the block’s semiconductor capacity — under a “Chips for Europe Initiative” included in the broader Chips Act. The Chips Act itself should result in additional public and private investments of more than EUR 15 billion.

- Where is the EU now: In 2020, the EU only occupied ten percent of the market share and even in that it lags behind in in its ability to produce cutting-edge semiconductors. After long discussions between Commissioner Vestager and Commissioner Breton, the EU is loosening its state aid regulation to facilitate public investments in the sector.

- Technological sovereignty: The Chips Act joins a series of initiatives to boost the EU technological sovereignty. The EU is not alone is attempting to gain more “sovereignty” over the production of core technological components. Improving the capacity to produce semiconductors is a must for the US and China, too, as it composes an increasingly fundamental element of competition between global actors.

Quick take: Doubts over the long-term resilience of the technological global supply chain to geopolitical developments and unforeseen events (such as the pandemic) make the Chips Act an important provision for the future of the EU. Nonetheless, the plan does not come without risks, the most concerning of which is the effect that such funding will have on the EU. Countries that are more advanced in chip design and production will attract large sums of these funds. In this case, Belgium and the Netherlands are likely to be significant benefactors. Consequently, should the investments only bring benefits to these countries, the Chips Act would then effectively increase the EU economic imbalance. This is an issue of which the Commission is all too well aware.

Read more:

EU-Africa Summit: Global Gateway with China in the background

The two-day EU-Africa Summit starts today in Brussels, bringing together leaders from the EU27 and 40 out of 55 member states of the African Union. The EU intends to use the summit to promote its Global Gateway (GG) initiative and to unveil a list of Africa-based projects in response to China’s activity in the continent.

What you need to know:

- GG preview: Ahead of the summit, between February 9–10, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen traveled to Morocco and Senegal (AU presidency incumbent). Von der Leyen unveiled the first GG regional package, focused on Africa, with plans to invest EUR 150 billion over the next seven years.

- China concerns: China’s sustained economic engagement with African nations remains a concern for Europeans. In a dedicated pre-summit statement, the chairs of eight European Parliament committees urged the EU to expand cooperation with the AU, citing China and Russia “advancing their geopolitical interests in Africa.” EU High Representative Josep Borrell echoed a similar tone highlighting that in Africa “other global powers competing for influence, much more than trade and investment is at stake.”

- Beijing’s scale-down: But as the EU ramps up its game, China seems to be streamlining its actions in Africa. At the November 2021 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), Beijing pledged USD 40 billion in investments, a third less than previously. Similarly, Chinese loans to African countries were slashed by more than two thirds between 2016 and 2019. However, Chinese participation in construction contracts remains stable or continues to grow while trade relations between China and African states reached an all-time high in 2021.

- Vaccine issue: Still, the summit may be overshadowed by the disagreement about access to vaccines (with average full vaccination rates in AU nations below 12 percent compared to the EU’s 71 percent). Despite requests by the AU, the EU is not willing to support a vaccine IP waiver that would support domestic production. Instead, the EU is expected to pledge EUR 1 billion to increasing manufacturing capacity and to share 700 million doses of vaccine by mid-year. The final pledges will be worth comparing with China’s pledges from FOCAC to provide 1 billion doses to African countries (600 million of which are to be donations).

Quick take:

The EU’s “responding to China” rhetoric, visible at the launch of the GG last year, seems to linger in preparations for the summit. It remains crucial for Brussels to keep the GG proactive and focused on the key concerns of the local partners and on a limited number of concrete projects that get delivered in partnership with local actors. It is important for the GG to go beyond reactively “outbidding BRI” and repackaging existing European initiatives. The political dynamics surrounding the summit together with the list of announced projects will be a litmus test of whether the GG lives up to those expectations.

Read more:

- European Commission: EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package

- Politico: EU tempts Africa away from Chinese influence

- Politico: Vaccine access puts EU and Africa at odds ahead of summit

- Project Syndicate (Josep Borrell): Europe Must Be Africa's Partner of Choice

- Quartz: Trade between Africa and China reached an all-time high in 2021

SHORT TAKES

The delayed EU-China summit is now expected to take place on April 1 in a virtual setting bringing together EU leaders and China’s president and premier.

According to French readout, on February 16, President Emmanuel Macron exchanged a phone call with President Xi Jinping urging him to lift trade measures targeting Lithuania and expressing concern over the situation in Xinjiang.

- Élysée [FR]: Telephone conversation with Xi Jinping

China agreed to participate in WTO consultations requested by the EU over China’s economic coercion towards Lithuania. Australia, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, the UK and the US formally requested to also join the consultations.

On February 9, China suspended imports of Lithuanian beef as per announcement by the General Administration of Customs — its first official economic measure deployed against Lithuania with other restrictions remaining informal.

China’s acting chargé d’affaires in Lithuania assured the deputy chair of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of Lithuania that, should Vilnius change the name of Taiwan’s Representative Office in Lithuania, tensions between the two countries would supposedly cease.

Belgian state security released a report warning that Huawei and Xiaomi mobile phones may be used for espionage purposes.

- The Brussels Times: Belgian state security issues spy-risk warning against Chinese smartphones

Polish President Andrzej Duda, who was the only European leader to travel to the Beijing Winter Olympics, met with President Xi Jinping to present a European perspective on the tensions in Eastern Europe. According to the Chinese readout, Poland is now set to become a hub for China-CEEC agricultural wholesale market.

- Ministry of the Foreign Relations of the PRC: Xi Jinping Meets with Polish President Andrzej Duda