The rise of geoeconomics and the need for a resilient European semiconductor industry

Globalization over previous decades has created economic interdependence between states allowing supply chains to benefit from cross-border openness and the division of tasks in production processes. The US-China trade dispute, however, has called these collaborative advantages into question. As part of the MERICS European China Talent Program 2020, Brigitte Dekker of the Clingendael Institute and Anna-Lena Rhiem of the Infineon Technologies AG examined the effects on the semiconductor industry – a key building block of nearly all high-tech products – and recommend a way forward for Europe.

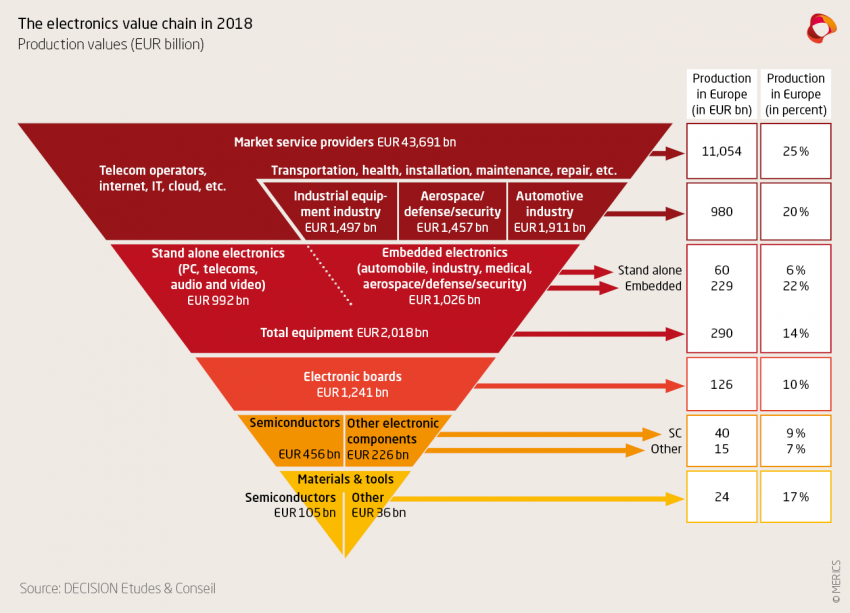

Semiconductor technologies play a pivotal role in most high-tech products (see Figure 1). However, the semiconductor industry has been particularly affected by current geoeconomic developments. While export control measures for semiconductor products are not new, President Trump took restrictions to the next level. After choosing a unilateral path in 2018 by introducing restrictions on the export of emerging and foundational technologies through its Export Control Reform Act (ECRA), the US administration then began pressuring European allies to cut off technology exports to China and actively limited the re-export of American equipment to third countries.

Being the world leader in software and chip design allows the United States to implement such unilateral restrictions, thereby exploiting chokepoints and exerting downstream pressure on foundries and integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) alike. These different types of players are each important – IDMs have design, manufacturing, testing and packaging capabilities whereas so-called “fabless” companies focus on chip design alone, collaborating with contract foundries (or “fabs”) to manufacture their chips.

The United States may have taken the lead, but it takes two to tango: one aspect of the US-China trade conflict has been the Chinese government’s politicization of key technologies. Indeed, the Chinese export control regulations that entered into force on 1 December 2020 are an unmistakable step to counterbalance Washington’s export control regime. Similarly, the Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures, issued on 9 January 2021, seek to undermine the US sanction regime. If individuals or companies are prevented from doing business by foreign law, the new regulation allows the Chinese government to release firms from compliance obligations. Moreover, Chinese companies that encounter losses due to the compliant behavior of foreign companies can sue for compensation in Chinese courts. For the semiconductor industry, the new rules represent more pressure to choose sides.

The attempts of both countries to limit each other’s innovation capability are accompanied by tremendous efforts to strengthen their respective local value chains. By 2030, Beijing wants to position its semiconductor industry as the world leader and meet 80% of domestic chip demand with domestic production. To achieve this goal, China has created several Integrated Circuit Funds, with a total funding volume of USD 150 billion.

In response, Washington is considering initiatives to strengthen its semiconductor industry at home. The CHIPS for America Act and the American Foundries Act were combined and passed as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) in December 2020. The legislation establishes the framework for a semiconductor incentive program to build new or re-equip existing fabs, and to expand federal spending for semiconductor research. Funding for the program still requires approval, but its target is USD 25 billion for fabrication capacity and USD 5 billion for research.

The European challenge – navigating global tech rivalry

Caught between Washington and Beijing, European semiconductor companies are having to navigate between techno-libertarianism and digital authoritarianism. On the one hand, Europe’s dependence on US software and chip design leaves European semiconductor companies vulnerable to export restrictions that limit their ability to trade with certain Chinese companies. On the other hand, China’s plan to become self-reliant obstructs fair competition and threatens European companies’ presence in the world’s largest semiconductor market – a market that consumed at least USD 211 billion worth of semiconductors in 2019. To stay competitive, Europe has to focus on its own technological resilience. Reaching this goal requires a multidimensional approach consisting of four steps:

- First, Europe should preserve its own technological choke points in order to become an indispensable partner and ensure continued access for European companies to key elements of the semiconductor supply chain. This includes increasing support for Europe’s world-leading equipment manufacturers like ASML, Trumpf or Zeiss, and blocking certain merger and acquisition activities that target European Intellectual Property and wafer supply.

- Second, policy makers and industry representatives should strengthen technology segments where European-based companies are already market leaders. While European-headquartered companies play a relatively minor role in the global semiconductor value chain – accounting for only 10 percent of global sales – they do occupy specialized niches within the market. With a strong focus on sensors, power electronics, embedded security solutions and security chips, firms such as NXP, Infineon, and STMicroelectronics have a dominant role when it comes to automotive, industrial applications, and encryption.

- Third, manufacturing capacities in Europe should be extended to reduce dependence on regions that are likely to be affected by geopolitical tensions. Considering the markets European-based companies address, this does not necessarily mean leading edge production but rather increased capacities down to 12 nanometer technology nodes. The technology node refers to the manufacturing process associated with a particular chip generation.

- Fourth, European players must become active in the field of emerging technologies at an early stage to shape developing markets and create new business opportunities. This applies particularly to artificial intelligence, connectivity and embedded processors. Here the quick transmission of R&D findings as well as chip and system design into mass production, where feasible, is important.

The importance of adequate funding

Fostering Europe’s technological resilience demands political awareness, sufficient foreign direct investment screening and financial support for key industries. The Joint Declaration on Processors and Semiconductor Technologies is an important step in pooling political efforts to strengthen development, design and manufacturing capabilities in Europe.

While the European Recovery and Resilience Fund is aiming to finance parts of the initiative, the Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI) framework will also play a role. It is currently the only compliant state aid regulation within the EU that allows funding for first industrial deployment activities or the construction of new fabs. It is also a well-established tool with the ability to deliver short-term results. Thus, IPCEI is a valuable instrument to address the four steps outlined above: funding can be used to support IDMs and equipment manufacturers, to build up or maintain production capabilities in Europe and to compete in the field of new and emerging technologies.

However, establishing IPCEI projects is heavily bureaucratic. For example, the newly implemented claw-back clause – a mechanism government authorities can use to reclaim granted and disbursed funding after the IPCEI is completed – overcomplicates the funding process and might withhold European companies from submitting ambitious projects that could enrich the European technology ecosystem.

To support the competitiveness of its own industry, the EU should focus on strengthening IPCEI as a funding tool. A simplified application process, clear responsibilities among EU institutions, no claw-back clause and sufficient funding on national and European level may achieve this aim and lead to greater technological sovereignty. Regardless of how the relationship between China and the United States develops, the trade conflict has exposed the fragile balance of global supply chains and highlighted the need for a resilient semiconductor industry.

-

Endnotes

-

1 ©2021 Gartner, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Gartner is a registered trademark of Gartner, Inc. and its affiliates. This publication may not be reproduced or distributed in any form without Gartner’s prior written permission. It consists of the opinions of Gartner’s research organization, which should not be construed as statements of fact. While the information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Gartner disclaims all warranties as to the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of such information. Although Gartner research may address legal and financial issues, Gartner does not provide legal or investment advice and its research should not be construed or used as such. Your access and use of this publication are governed by Gartner’s Usage Policy. Gartner prides itself on its reputation for independence and objectivity. Its research is produced independently by its research organization without input or influence from any third party. For further information, see Guiding Principles on Independence and Objectivity.

About the authors:

Brigitte Dekker is a Junior Researcher in the Clingendael Institute’s EU & Global Affairs Unit and the Clingendael China Centre.

Anna-Lena Rhiem is a Public Affairs Expert at Infineon Technologies AG where she works on security and technology policy with a focus on China.

The authors participated in the sixth annual MERICS European China Talent Program in December 2020, during which parts of the argumentation presented in this blogpost were developed. The authors bear sole responsibility for the content.