Get yourself a job: Beijing’s measures to tackle rising youth unemployment

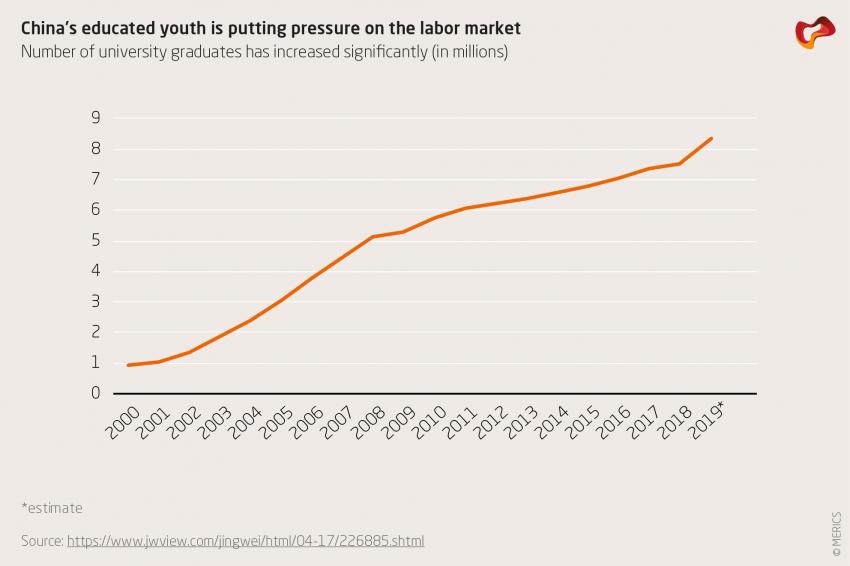

In 2019, an estimated record number of graduates will enter China's labor market – and there are indications that many will struggle to find a position. How does the country create jobs for the 8.34 million students who will graduate from its universities this year? To deal with the challenge, different regions have been experimenting with different solutions.

Looking at China’s official labor market statistics, all seems well: The latest surveyed unemployment rate in urban areas fell to five percent from a peak of 5.3 percent in February. Likewise, the ratio of labor demand to supply remains close to historic high levels of 1.28. For the first five months of the year the government claims to have created 5.97 million urban jobs, up 20 percent from the same period last year. As in previous years the government seems well on track to reaching its annual target of eleven million new urban jobs.

Given this rosy picture, why then did Beijing create a new leading small group (LSG) for exactly this topic? LSGs are normally only established for major tasks that are particularly challenging. Yet in May, a State Council Employment Work Leading Group was set up, headed by Vice-Premier Hu Chunhua. Its 25 members are the vice leaders of nearly every ministry and institution. Its task: “researching as well as solving the major problem of employment.”

There is a sense of urgency among China’s leadership

Despite the seemingly strong labor market data there is clearly a sense of urgency among China’s leadership. Employment policies have been elevated to the status of macroeconomic policy by the government for the first time. In part this has to do with a more long-term structural transformation in the labor market, including technological change, but it also has to do with the current economic slowdown.

Indeed, data from non-government sources suggests a more challenging picture. According to China’s Institute of Economic Research (CIER), overall job offerings fell by 7.6 percent, while job seekers grew by 31.1 percent in the first quarter of 2019, lowering the overall ratio between supply and demand from 1.91 last year to 1.68. The Purchasing Managers’ Index sub-index on employment has fallen to the lowest level since 2009 for manufacturing and is nearing the historic low for the service sector.

At the Summer Davos meeting in China’s northern city of Dalian on July 2, Han Jian, an associate professor with the China Europe International Business School, spelled out the potential impact on employment of the ongoing tensions with Washington, with estimated job losses ranging from 500,000 in the best-case scenario to 27 million in the worst case, according to different institutes’ calculations. However, demand for labor had already started falling before the trade war began, caused as much by the slower growth in GDP, a slowdown in the previously booming internet service sector, and by efforts to reign in risks in the financial sector. According to China Market Research Group more than 80 per cent of companies hiring graduates were not advertising for new staff. And more than half had reduced their openings, with banking worst hit.

Still, new businesses in the internet and mobile internet sector have created some 30 million jobs, which, according to Han, indicates that China should be fine. Yet what Han highlights here is both a core feature of China’s employment policy for graduates and a structural problem of the labor market. How does the country create jobs for the 8.34 million students who will graduate from its universities this year? Different regions have been experimenting with different solutions. The province of Jiangsu, for example, is offering students the opportunity to apply for a two-year social service-related job. In Beijing, meanwhile, one key solution for the country is to allow the record number of graduates in 2019 to become self-employed and, ideally, drivers of mass innovation. Described as “big masses create employment (=businesses), ten thousand masses create innovation (大众创业,万众创新)”, the policy was initiated by Premier Li Keqiang in May 2014.

Graduates end up in jobs with salaries that are a far cry from their expectations

The city of Tianjin, by contrast, has decided to focus on offering special support for young graduates between 16 and 35 who have been unemployed for over a year. Among the offerings are guided tours through start-up parks, meetings with potential investors and access to specific seed funding.

The results of these employment initiatives are not easy to assess given the fierce competition in the start-up sector and the frequent race-to-the-bottom in terms of pricing, particularly in industries such as food delivery and transportation. Making a decent living in the medium term might remain a distant dream for many of those who have founded start-ups or are employed in these service industries.

This also reflects changing expectations among the young urban middle class. Many graduates end up in jobs with salaries that are a far cry from their original expectations. According to the online job platform Zhaopin, while a third of graduates are looking for monthly salaries of between 6,000 CNY (US$868) and 7,999 CNY (US$1,158), only 18 percent actually achieve this, adding to the social pressure young graduates face in finding adequate jobs. The problem, it claims, lies in a stark mismatch between what companies are looking for and what the labor market offers. For instance, even though demand for employees in the intermediate services sector increased by 25 per cent, applications from graduates declined 21 per cent.

Growing dissatisfaction has led to the creation of a small youth movement

It is not only that there is a mismatch in terms of sectors, but also in terms of expertise requirements and choice of lifestyle. Take the example of software engineers: Companies like Jingdong or Tencent offer up to 700 CNY per hour, yet still they struggle to find suitably qualified candidates. Meanwhile, the recent public outcry by young IT engineers, following Jack Ma’s call to enjoy working hard from 9am to 9pm six days a week, is a clear indicator that there is also a mismatch in terms of lifestyle expectations.

Growing dissatisfaction and disappointment among graduates have led to the creation of a small, but nevertheless active group of young “leftist” students in Southern China who are committed to improving labor rights and workers’ rights. Beijing is worried that this youth movement could form potential alliances and bring graduate employment perspectives to the top of the agenda. If unemployment levels among middle class graduates grow, the structural problems in the employment market could turn into a larger socio-political crisis that Beijing would struggle to control.

This article is part of the latest issue of the MERICS Economic Indicators, a project monitoring China's economic development.