Export controls: China’s long game to defend its tech advantage

Rather than abruptly pulling the plug on certain exports, Beijing is gradually sharpening an instrument to better control global tech supply chains and pursue a range of other goals, says Rebecca Arcesati. This article is part of our series on China’s strategies to reduce vulnerabilities.

Amid intense geopolitical and technological rivalry, Beijing has recently shown readiness to use its advantage in supply chains to deter rivals like the US and Europe from blocking access to key technologies. Chinese leaders appear intent on consolidating China’s dominance over so-called “stranglehold technologies” where it can make itself indispensable. In 2020, President Xi Jinping remarked that the country “must tighten international production chains’ dependence on China, forming a powerful countermeasure and deterrent capability against foreigners who would artificially cut off supply [to China].”

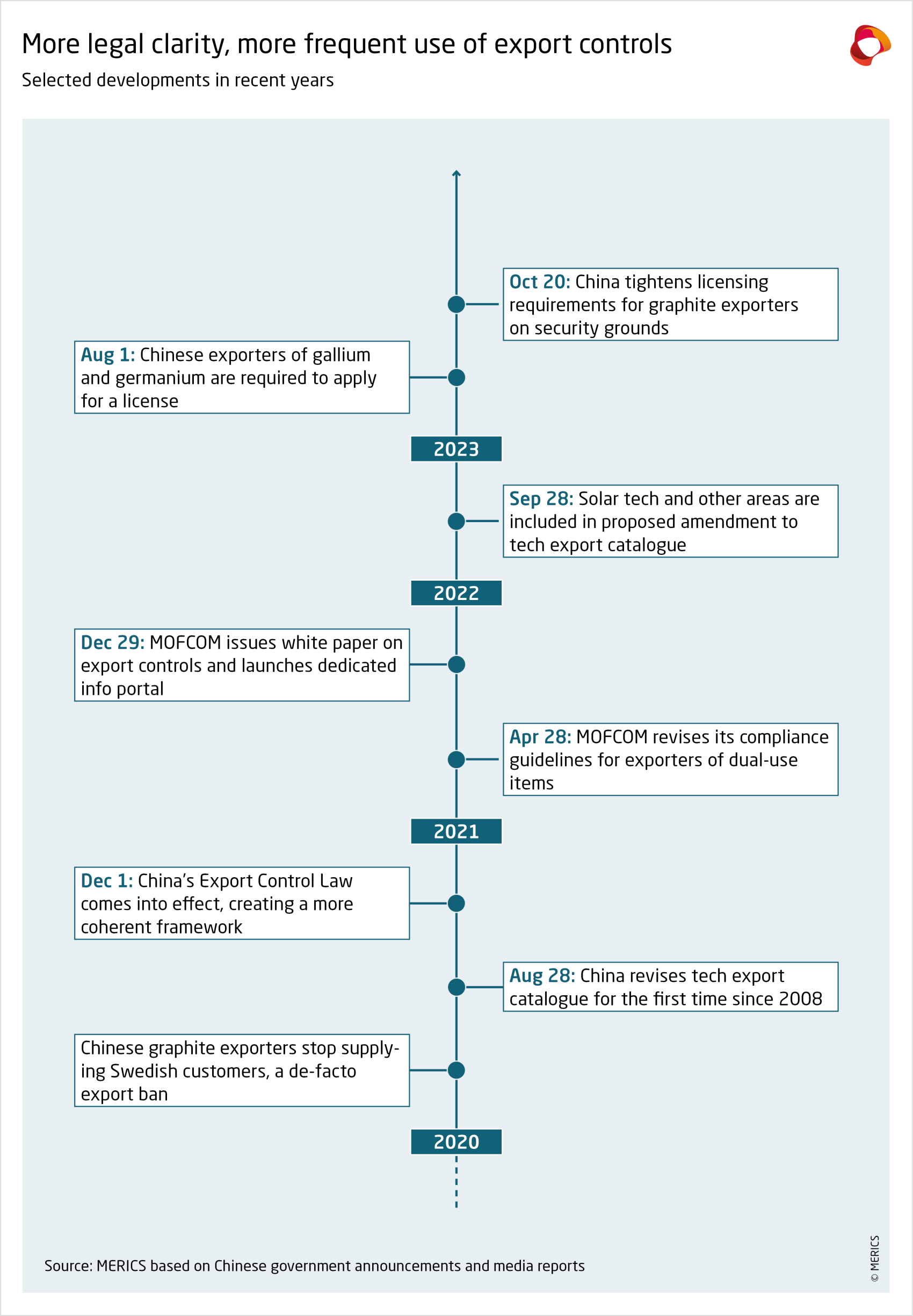

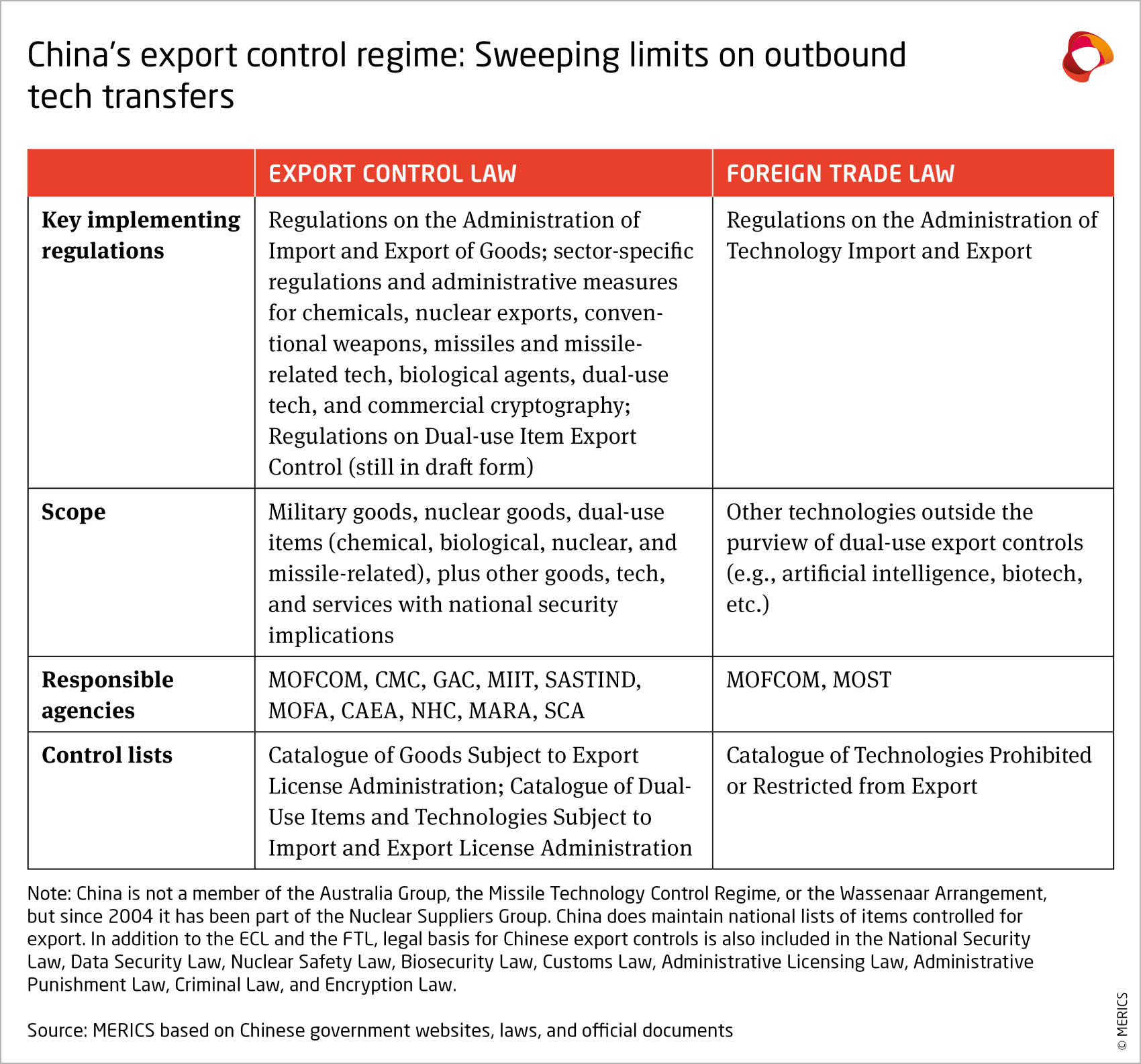

Chinese policymakers use export controls to protect military, economic, technological, and industrial security. These have evolved rapidly over the past few years. From Beijing’s perspective, export controls can serve a range of objectives beyond preventing technology use in military applications. They can project a credible threat of retaliation and deter other countries from diversifying supply chains away from China.

For Beijing, this is mainly but not exclusively defensive posturing. It is a long game that liberal market economies would be wise to take seriously. Rather than abruptly pulling the plug on certain exports, China’s government is gradually sharpening an instrument to better control global tech supply chains and pursue a range of other goals.

China’s ace in the chip war

Chinese export controls came into focus in summer 2023, when the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) announced new licensing requirements on the export of gallium and germanium, critical minerals in semiconductor manufacturing. Some saw this as a response to the Dutch government’s new export restrictions – under pressure from the US – on products made by ASML, a major supplier of chipmaking tools to China. And retaliation it was – just not in a simple, tit-for-tat manner, and likely not aimed at that target.

If the past year is of any indication, it is plausible that these mineral controls – which do not constitute an export ban – were chiefly aimed at US companies. While germanium is used in fiber optics and solar panels, and gallium in consumer electronics and 5G telecommunications, both are key for the aerospace and defense industries. In 2023, the Chinese government added US defense contractors Lockheed Martin and Raytheon to its Unreliable Entities List – companies China marks for punitive action. It also deemed memory chips from US defense contractor Micron to pose a risk to its domestic critical information infrastructure.

Just as Washington’s export controls seek to kneecap military modernization by curtailing China’s capabilities in semiconductors, artificial intelligence and supercomputers, Beijing could be doing the same with strategic defense minerals. China’s leaders would likely assert its latest controls are actually a measured response to the Biden administration’s muscular strategy of containing China’s technological progress.

Shoring up China’s industrial dominance

China also uses export controls to prevent others from building alternative supply chains that threaten its industrial and technological leadership. The EU, US and others have grown uneasy with China’s dominance in the value chains of many products needed for their low-carbon transition, such as batteries, high-performance magnets, electric vehicles (EVs), solar photovoltaic (PV) modules, and fuel cells. Losing this indispensability would erode China’s strategic and geoeconomic leverage.

If G7 economies want to de-risk from China, Beijing will not let them do so easily with raw materials and technology it supplies. China enjoys a strong upstream advantage in many areas, like graphite, of which it is the world’s top producer and exporter. In October, MOFCOM announced some changes to existing dual-use licensing requirements for some types of graphite. In the past, China reportedly already withheld some graphite exports from Swedish producers of lithium-ion battery cells. The new measures specify synthetic graphite, needed for battery production, just weeks after the European Commission announced an anti-subsidy investigation into imports of battery EVs from China. Retaliation and the defense of industrial interests can go hand in hand.

Crucially, supply chain security goes beyond raw materials. It also includes technology and intellectual property required in mining, refining, and manufacturing processes. In proposed amendments to its Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited and Restricted from Export, Chinese authorities initially mulled new licensing requirements for technology needed to make solar wafers for PV panels. They then dropped those changes in the final version of the amended catalogue, but proceeded to ban the export of technology used to process rare earths and manufacture magnets from them.

Implications for Europe

Chinese policymakers seem to view export controls as a versatile instrument. Xi has relentlessly expanded the Chinese Communist Party’s definition of national security, consistent with the party’s longstanding preoccupation with staying in power. But it also reflects an ever more paranoid perception of threat. As such, predicting how Beijing may mobilize its evolving arsenal of defensive and retaliatory measures can be difficult for foreign actors. Still, viewing China’s use of export controls through the lens of its defensive core interests may help policymakers and businesses figure out where it may hit next and devise appropriate strategies.

Some Chinese export controls will have more bark than bite, and weaponizing export licenses may end up hurting China’s interests the long-term in areas where it still relies on foreign inputs, or where alternative sources of supply exist. Regardless, European governments must prepare for Chinese decisions based on interlocking national security, industrial and technology policy objectives.

Considering the EU’s dependence on China to supply critical inputs for its digital and green transitions, strategies should focus not only on alternative sources for critical raw materials, but also on developing technological capabilities and identifying areas where China relies on Europe and partners. China wants to remain indispensable. Perhaps Europeans should take a page from this strategy.

This article was first published by China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE) on December 14, 2023.