Is ageing China facing a Japanese-style “lost decade”?

Before we write off China’s economic dynamism for a decade, we should consider the significant ways in which it differs from Japan. Differences in the timing of demographic change in the two countries in particular suggest that China’s experience will not mimic Japan’s. With appropriately targeted polices, China will avoid a “lost decade.”

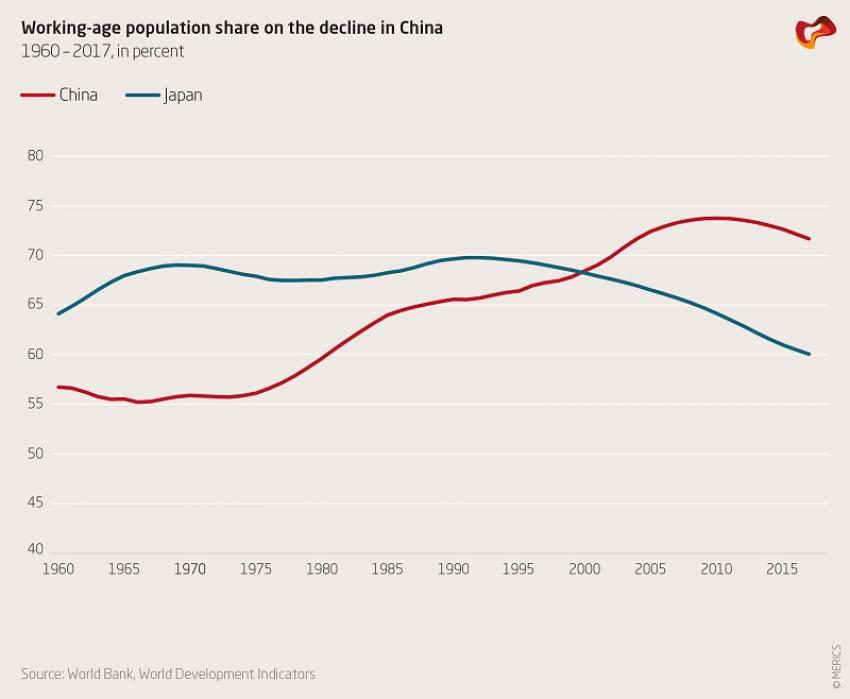

China’s leaders have recently set a growth target for 2019 of 6 -6.5%, marginally lower than the target of 2018. Intensifying population ageing is one factor attributed to fears of an emerging Chinese ‘lost decade’, akin to Japan from the mid-1990s. The comparison is especially worrying in that like Japan then China today sits mid a trade war with its most important economic partner, the United States. Lesser obviously, like Japan then, China sits a few years past its peak workforce population share (Figure 1).

Population ageing and the economy

An ageing population poses many economic challenges: rising labor scarcity in sectors and regions where labor was once bountiful; fiscal and corporate resources increasingly directed towards pensions; more human capital directed toward caring for the old. In other words, national resources are diverted away from more productive economic endeavors.

Demographers use several different definitions for population ageing onset. China passed all the leading such indicators between 1987 and 2002. China’s workforce population share has meantime been in decline since around 2011 (Figure 1) when the workforce peaked at some 925 million workers. Despite the onset of later stage demographic transition, however, China’s per capita income remains that of just a middle-income country.

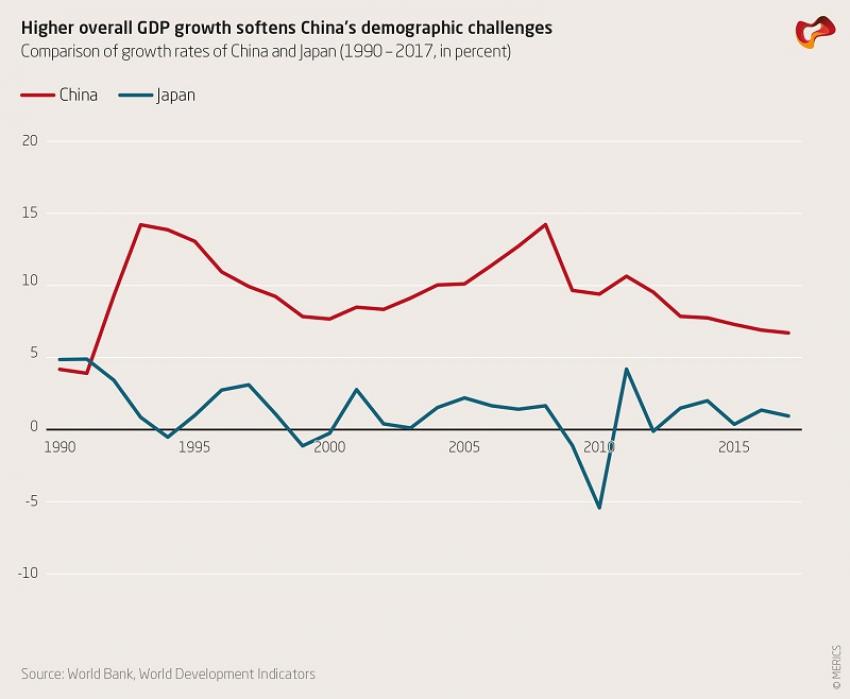

Although China is old before it is rich, it hence retains convergence growth potential. GDP is still growing at some 6% annually (Figure 2). This means the resource envelope available to households and the government is also growing at a relatively fast rate.

Japan, on the other hand, was already an advanced industrial economy when its population ageing intensified, amid a more established slower, steady state growth rate.

China experiencing demographic transition as a developing country in turn means the economic impact of population ageing is likely to be different to the Japanese case.

Ageing in developed Japan vs developing China

Digging into the demographic data reveals other key differences. Whereas in Japan the older cohort dominated the economic agenda through their adulthood, in China the older generation have never – not even in their prime – been important drivers of consumption. Just as China puts greater emphasis on consumption as a new growth engine, it meets a newly enriched, higher-spending younger consumer class for whom a more affluent level of consumption has been a relatively norm from the get go. In Japan, in contrast, the lost-decades younger cohort feels less economically prosperous than the older population segment.

In the same way, when the older Chinese generation leaves the workforce the impact will be different. Unlike in Japan where the education gap between generations is narrow and the human capital embodied in the older cohort deep, in China human capital is dramatically skewed in favor of the young. The lower fertility rate from the 1970s combined with rising household and national incomes means that over recent decades dramatically more resources have been invested in each child’s education. As China’s population share of workers falls, just maintaining output per capita requires improved productivity per capita. China’s younger cohort, at least theoretically, are well-positioned to utilize their relative skills to maintain, if not increase, productivity levels.

Finally, China’s dependency ratio, as measured by the ratio of youth (<15 years) and elderly dependents (>64 years) over the total working population (aged 15 to 64) will remain lower than Japan’s for some years to come. Both countries have persistent below replacement level fertility, but Japan’s demographic transition process began earlier and so the trends are more established. Japan moreover, has one of the longest life expectancies in the world, and is already home to some 70,000 centenarians, ranking it among a handful of super-aged societies.

Ageing with Chinese characteristics

China may not be facing a “lost decade” akin earlier Japan, but it nonetheless must overcome its own challenges. As a developing country, it still retains pockets of poverty. Eradicating these requires consuming fiscal resources. It also awaits to be seen if the younger cohort are sufficiently educated to realize elevated national per capita productivity.

Pension sustainability is also a major challenge. The 2019 Work Report promised to reform the management of aged-care insurance funds and guaranteed the payment of pensions on time and in full. In March, the Ministry of Finance transferred a nearly 7% stake in the People’s Insurance Company of China into the state pension fund. This is one step in what is expected to be a standard pattern as China sets aside assets to cover its emerging pension-related liabilities. New opportunities in the sector are also emerging for foreign investors.

Avoiding the downward pull of an ageing population will not be easy. In April China’s State Council released a set of Opinions on promoting the development of pension services, which set out 28 policy proposals for addressing a breadth of issues presently or imminently expected to affect ‘ageing’ China.

There are grounds for hope that, given the right policies, China will not suffer Japan’s recent fate. Whether it succeeds or not otherwise, only time will tell.

This article is part of the latest issue of the MERICS Economic Indicators, a project monitoring China's economic development. It is based on Johnston, L.A. (forthcoming). The Economic Demography Transition: Is China’s “not rich, first old” circumstance a barrier to growth? Australian Economic Review (to be published in a 2019 issue).